‘Twixt the Soft & Hard Femme Fatale

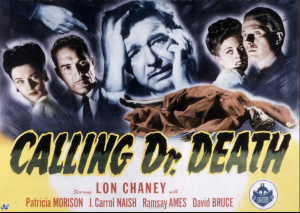

Calling Dr. Death

Introduction

Although Street of Chance was released in November 1942, its time of production was from 16 January to mid-February of that year. Calling Dr. Death, the next crime noir with a femme fatale, was produced 20 months later, from 25 October to mid-November 1943, and released on 17 December. The specific timing of its production and release, plus the relatively long time-lapse following the production of Street of Chance, may explain the unusual femme fatale in Calling Dr. Death, who is neither clearly “soft” nor “hard.”

For my extended discussion about the “soft” femme fatale and the “hard” femme fatale, see the page International Lady.

Main Credits

Director: Reginald Le Borg. Screenplay: Edward Dein. Producer: Ben Pivar. Cinematographer: Virgil Miller. Music: Paul Sawtell. Art Directors: Ralph M. DeLacy, John B. Goodman. Editor: Norman A. Cerf. Cast: Lon Chaney Jr. (Dr. Mark Steele), Patricia Morison (Stella Madden), J. Carroll Naish (Inspector Gregg), David Bruce (Robert Duval), Ramsay Ames (Maria Steele), Fay Helm (Mrs. Duval). Released: Universal Pictures, December 17, 1943 (US). 63 minutes.

Presentation

Stella Madden, RN, is the first femme fatale in a crime noir who is after money and gets some. How this money comes her way isn’t explicitly told. Yet, comments (clues) in the film enable us to deduce it.

Like the soft femme fatales in crime noirs, 1940-1942, Stella seems to be in love with a man, her boss, Dr. Mark Steele, a neurologist who is adept at hypnotism. But, as we will see, her actual feelings for Steele may be called into question. What is certain is that Steele loves her. As for his marriage to a beautiful wife, Maria, he knows it is on the rocks. In fact, she is having an affair with an architect, Robert Duval…until she is bludgeoned to death with a fireplace poker and her face is disfigured with acid. Duval is arrested, convicted and sentenced to death.

When Steele visits Duval in jail, he asks the prisoner how he met Maria.

“What were the circumstances?”

Duval replies, “I’d been rather successful. Then I began to gamble. I lost everything, everything I’d built up. Fifteen years of success went overnight. Then I met Maria. I didn’t pay much attention to her until your name was mentioned. Then it suddenly dawned on me how successful you’d been. Maria didn’t mean anything to me. I was desperate for money. I’d have done anything. We went out together a few times and then, when I was sure of her, I told her I was in trouble. It wasn’t hard. In a few months she’d given me ten thousand dollars. I thought after I got the money, I’d leave her, but it wasn’t that simple. She got under my skin. I kept away from her for a few days, then I realized I loved her.”

“Did you return the money?”

“Half of it.”

“What about the rest?”

Duval doesn’t respond.

“How about the rest?” Steele says loudly. Then he thinks to himself, “He’s obviously shielding someone. But who? His wife?”

In the film’s climax, Steele hypnotizes Stella. With spectacular noir visual style, her memories are presented like brief dream sequences. In the first, Duval confronts Stella.

He says, “I’m returning the money Maria gave me.”

She retorts, “Don’t be a fool! The doctor doesn’t know a thing about it. I fixed the records. We’re in the clear.”

“Give me back your share. I’m returning that, too.”

“I won’t. You’ve got yours. I’ve got mine, and I’m going to keep it.”

“Oh, no you’re not. Maria means too much to me. Even if I have to tell the doctor.”

“Tell the doctor? You wouldn’t dare!”

“I love her. I’d do anything…even tell the doctor.”

“Oh, no, you’re not going to tell him. He belongs to me. I planned all this. Don’t interfere. I’ll see you dead first.”

Duval slaps Stella’s face and walks off.

In her second memory, shown in silhouette, we see Stella repeatedly strike Maria with the poker and then throw the acid on her.

In her third memory, Stella manipulates Steele into providing evidence that Duval murdered Maria. Because he can’t recall his whereabouts when Maria was killed, Steele hypnotizes himself, and in that state Stella plants a narrative in his mind that makes him believe Duval is the killer. While still hypnotized, he obeys Stella’s command to “repeat” that narrative aloud, which she records.

In her fourth memory, we hear Stella’s reaction when Steele tells her that, because she is overworked being his nurse, secretary and bookkeeper, he wants her to “get a girl to take care of the office. As a nurse, I can’t replace you.” She thinks to herself about Steele, “I mustn’t let you go through the files. I mustn’t let you see the canceled checks for the money Maria gave to Duval. Mustn’t let you find out. Mustn’t let you see the canceled checks.”

When Stella tells Duval in the first memory, “I fixed the records,” it means, as we learn in her fifth, she set off a fire in the doctor’s office that not only can’t be traced to her but also burns up all the “canceled checks.” This eliminates the evidence that Maria had been giving money to her lover. And, as we know from the fourth memory, Stella does this to prevent Steele (and the new bookkeeper) from discovering that she, as the previous bookkeeper, must have known about these payments but never told Steele about them.

One way to explain why Duval was splitting Maria’s money with Stella fifty-fifty is that he was buying Stella’s silence.

Yet, there is a better way. It is based on Stella’s boast to him that she “planned all this.” I believe this implies Duval lied to Steele. He never “lost everything” because of his gambling. For instance, his wife, confined to a wheelchair for the past year, tells Steele that she loves her husband; she doesn’t say that he had gone bust. (Perhaps to prevent Mrs. Duval from revealing something, Stella twice tries to keep her from speaking to Steele; and the second time she succeeds.)

I suggest Stella was the brains behind a con game Duval played on Maria. Duval never tells Steele the actual “circumstances” in which he met Maria. He says when Steele’s “name was mentioned,” he realized she must have money. Instead, I think that Stella, being aware Steele is well-off, came up with the scheme for Duval to “meet” Maria and, when he “was sure of her,” to start hitting her up for money. Of course, Duval had to share what he got with Stella; and he doesn’t tell Steele the truth about how he met Maria because, as Steele thinks, “He’s obviously shielding someone,” namely Stella.

The fly in Stella’s ointment is that Duval eventually falls in love with Maria. To improve his prospects for getting her, he wants to return the full $10,000. (His hopes are dashed when, the night she is murdered, Maria makes it clear to him that she has only been toying with his affections. Previously, she has told Steele he won’t ever be able “to get away” from her because, “I like my title, the doctor’s wife. I have money, position, and there’s nothing you can do about it!”)

What would strengthen the case that Stella and Duval worked together to swindle Maria is if there were evidence they knew each other. And there are clues that this is so. While hypnotized, Stella’s first memory begins at night on an empty street. As she hears, “Stella,” called out over and over, she turns and walks in one direction and then another. When she steps past an alley, Duval emerges, and the exchange quoted above takes place, with that tell-tale remark, “We’re in the clear!” Doesn’t this suggest they were in collusion? Doesn’t it give credence to Stella’s claim to having “planned all this,” in which “this” is getting money from Maria?

Whether Stella intends all along to frame Duval for Maria’s murder isn’t revealed. Perhaps she makes him the fall guy because he threatens to tell Steele that she won’t give back the $5000. (In her first memory, she warns Duval, “Don’t interfere. I’ll see you dead first.”) Regardless, Stella can’t know in advance that Steele will want to hypnotize himself, thereby providing her with the opportunity to help the doctor establish an alibi for the night Maria was killed as well as incriminate Duval. What Stella has Steele say is that when he left his lodge, Maria was still alive and, as he drove away, he saw Duval go inside. Since Inspector Gregg considers this unreliable evidence, he tells Stella and Steele that he won’t use the recording. (When Duval is arrested, he tells Steele that after he had a quarrel with Maria, he left her and he drove all night. He says, because he “had no proof” for his story, “the police didn’t believe him.” However, no reason is given to explain why the police picked him up in the first place. At his trial he is convicted on “circumstantial evidence,” and whatever that evidence was isn’t mentioned.)

Adding to the plot’s murkiness, there is evidence that Stella doesn’t want Duval to be executed. After Steele reads to her from a newspaper, “Governor denies Duval reprieve; Duval must die,” she faints. This causes Steele to say she is overworked and she should “get a girl to take care of the office,” which leads to her burning up Maria’s canceled checks. In her sixth and final memory, Duval is walking toward the electric chair when he is replaced by Stella, who screams, “Don’t let them do it, Mark! Don’t let them! Mark!” And with her last scream, Stella comes out of her hypnosis. Her memories/confessions have not only been heard by Steele but also by Inspector Gregg, who arrests her for Maria’s murder. Right away, before Duval is executed, Gregg calls the warden at the prison to clear Duval and save his life.

What does it all mean? How does Stella know Duval? Was their relationship strictly business or, given his wife is paralyzed and he isn’t initially romantically interested in Maria, were they having an affair? Although she fabricates evidence against Duval (which Inspector Gregg doesn’t introduce), was she counting on Duval getting a reprieve and, when it is denied, is that why she faints? The answers, which the film doesn’t provide, would go a long way toward settling whether Stella is more a soft femme fatale than a hard femme fatale…or vice versa.

Why is there this conundrum? Because I believe Stella is a transitional femme fatale. On the one hand, we might say her love for Steele and her murdering Maria from jealousy are the behavior of a soft femme fatale. On the other hand, we might say Stella is a hard femme fatale because she masterminds a scam, destroys the evidence of how the ill-gotten money is obtained, and manipulates Steele into testifying that Duval is the killer (to help to send him to the electric chair and keep him from exposing her to Steele). But wait! Does she really want Duval to be executed? If not, then this, too, is the behavior of a soft femme fatale. Wait again! Does she really love Steele? She tells Duval that “he’s mine,” and she kills Maria. Perhaps she only cares about having what Maria had: the title of being a doctor’s wife, money, position. The plot prevents a conclusive interpretation of Stella as soft or hard.

Although the opaqueness of the plot contributes to the ambiguity in Stella’s character, in one key aspect Stella differs from all but one of the prior soft femme fatales in crime noirs: she commits premeditated murder. She goes to the lodge where Maria is staying, and she brings the acid with her. Consider the circumstances for the following killings. (For a plot summary of each film, see the section, Soft Femmes Fatales in Crime Noirs, 1940-1942, in the page International Lady.)

They Drive by Night (1940) – taking advantage of an unforeseen opportunity

The Letter (1940) – impulsively responding to rejection

Blues in the Night (1941) – taking advantage of unforeseen opportunity

Street of Chance (1942) – by accident

Only in The Maltese Falcon is the murder also premeditated. However, the production of The Maltese Falcon was completed over 27 months before that of Calling Dr. Death began (9 June – 18 July 1941 vs. 25 Oct. – mid-Nov. 1943) During this interval America was leading the Allies to victory in the Second World War, and social relations between the sexes at home were about to be phenomenally transformed. Seen in historical context, it is understandable that, even as a killer spider woman, Brigid O’Shaughnessy brooks no comparison with Stella Madden in deviousness, cunning and viciousness. Furthermore, as a consequence of this changing historical context, Stella is distinct from the soft femme fatales who precede her. She is a fascinating, if scary, harbinger of the hard femme fatale, soon to appear on screen and then become – unjustifiably, according to the evidence in the filmography of the Classic Era (1940-1959) – the consensus paradigmatic female character in US film noir. (See the pages Significance of the Woman in Distress and Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale.)