Florey: First Director of Many Noirs

Once the following two conditions are acknowledged, Robert Florey must be recognized as the first director with an extensive noir filmography.

1. Film noir begins prior 1940.

2. Film noir consists of spy noirs as well as crime noirs.

For an explanation of these two conditions, see the page Spy Noirs & the Origins of Film Noir.

Below is Robert Florey’s “noirography” through 1941. During these years no other director’s noirography, of any country, comes close to that of this French-born man with a US career. Also, note that the only significant appraisal of his work is Brian Taves’s Robert Florey: The French Expressionist.

There are two reasons why Florey established such a large noirography so early.

First, by the late 1930s, he was constantly making crime films and spy films. Taves says, “The thriller was the genre in which Florey was most profitably and most prolifically employed. Most of these films were made in the 1930s, particularly at Paramount, where nearly every picture he made was of this type.” (p. 9)

Second, in most of these films there is a noir visual style. From the title of his book and throughout the text, Taves emphasizes the “expressionism” in Florey’s work.

“No term appears more frequently in this study than expressionism, and that is because no style had more influence on, or is more apparent in, Florey’s canon…The influence of expressionism was strongest on Florey in the late 1920s through the 1930s; by the 1940s it had begun to wane and appeared only periodically in his big-budget movies and television work.

“Florey’s expressionism consisted of a number of elements descended from German cinema of the 1920s. Most prominent was a fondness for shadows and dark compositions, often emphasizing contrasts of light and shade. His frame compositions were frequently unusual and artistic, and he used the subjective camera often and effectively.” (pp. 30-31)

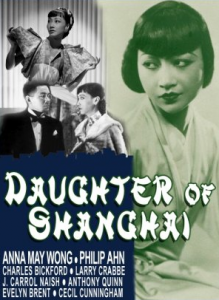

As one example, take Daughter of Shanghai (1937), which starred Anna Mae Wong.

In his plot summary, Brain Teves says:

“Daughter of Shanghai was a quickly-paced topical exploitation thriller dealing with the always timely subject of illegal immigration…Wong portrays the daughter of a Chinatown art dealer who is killed when he refused to employ illegals in his business. Vowing to destroy those who murdered her father, she brushes the police aside [and an FBI agent played by Philip Ahn] and sets out to uncover the smuggling ring herself. Trampling on expectations and stereotypes, she proves herself intrepid and courageous.” (p. 206)

Taves assesses the film’s mise-en-scène as follows.

“The direction, set design, and photography are well above the “B” level and the perils-of-Anna type plot…The photography is extremely dark, as if taking place entirely at night, with only a few interiors well illuminated. This produces a sense of menace and uncertainty in every scene. The limited lighting allows for very creative effects; for example, the action of a fight is seen only as shadows crossing a close-up of Wong’s face. Many clever camera angles enhance the mystery and punctuate moments of high suspense, particularly in the café sequences. The décor and design of the sets contribute to the sense of semi-realism which the story relies upon for dramatic effect, while at the same time effectively capturing Wong’s Oriental allure.

“Another quality distinguishing Daughter of Shanghai is the sense of mood and atmosphere evoked in Florey’s direction, both in the Chinatown setting and particularly in Port O’Juan. This is an exotic, tropical island somewhere off the coast of the Americas, a haven for outcasts and lawlessness. Here, in a setting reminiscent of von Sternberg, the aliens gather to be transported to the United States. On the island is a steamy café where Virginia Dobson and later Wong perform mesmerizing dances to the leers of a disreputable-looking audience, including a pet monkey.” (p. 207)

There are two other aspects about the plot of Daughter of Shanghai that should be mentioned, one that would recur in spy noirs, and one that is unique. The smuggling-ring leader is an elderly woman, played by Cecil Cunningham. (For more about such women, see the page Spy Noirs & the First Femme Fatales.) The film ends with a romantic coupling between the two Asian-American leads, Ahn and Wong. Furthermore, his marriage proposal and her acceptance are spoken in Chinese.

Wong’s character, which Taves describes as “intrepid and courageous,” is one of many such strong women in Florey’s films, whether they are noir or not. He says:

“An unusual element in Florey’s movies – particularly considering they came from a Frenchman and a director who worked mostly in the 1930s and 1940s – was the strength of his female characters. If one looks at the films where women play large roles, it becomes clear that in nearly all these pictures women prove to be intelligent, courageous, and seldom submissive to men; there are very few wholly subservient women. No consistently more commanding group of women appeared than those of his spy movies. Gertrude Michael, Ina Miranda, Nancy Coleman, and Marta Toren of Til We Meet Again, Hotel Imperial, Dangerously They Live, and Rogues’ Regiment, respectively (and even, to a lesser extent, Rochelle Hudson in Meet Boston Blackie), were every bit as clever and often more forceful than their male counterparts. Even in his gangster and mystery thrillers, genres where women usually play insignificant or weak parts, his female characters were often the protagonists or almost equally important to them. Examples include Anna Mae Wong in A Study in Scarlet, Daughter of Shanghai, and Dangerous to Know; Ellen Drew in Women Without Names and The Crooked Way; and Gail Patrick in Dangerous to Know, King of Alcatraz, and Disbarred.” (pp. 16-17)

Where appropriate I have cited the names of the following authors of extensive reference books when they cite specific films by Florey as noir: John Grant, Michael Keaney, Spencer Selby. All other selections are my own.

1932: Murders in the Rue Morgue (crime noir)

1936: The Preview Murder Mystery (crime noir)

1937: Outcast (crime noir)

1937: Daughter of Shanghai (crime noir)

1938: Dangerous to Know (crime noir)

1938: King of Alcatraz (crime noir)

1939: Hotel Imperial (spy noir)

1940: Parole Fixer (crime noir; sourced: Grant)

1940: Women Without Names (crime noir)

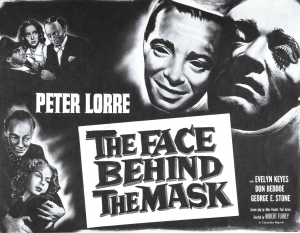

1940: Face Behind the Mask (crime noir; sourced: Grant, Selby)

1941: Meet Boston Blackie (spy noir; sourced: Grant)

1941: Dangerously They Live (spy noir; sourced: Grant)

Robert Florey’s noirography continues as follows:

1942: Lady Gangster (crime noir; sourced: Grant, Keaney)

1944: Roger Touhy, Gangster: (crime noir)

1945: Danger Signal (crime noir; sourced: Grant, Keaney, Selby)

1946: The Beast with Five Fingers (crime noir; sourced: Grant, Selby)

1947: Monsieur Verdoux (crime noir; sourced: Keaney)

1948: Rogues’ Regiment (spy noir)

1949: The Crooked Way (crime noir; sourced: Grant, Keaney, Selby)

1950: Johnny One-Eye (crime noir)

1950: The Vicious Years (crime noir)

Bibliography

John Grant, A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Film Noir: The Essential Reference Guide (Limelight Editions, 2013)

Michael F. Keaney, Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959 (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003)

Spencer Selby, The Worldwide Film Noir Tradition (Sink Press, 2013)

Brain Taves, Robert Florey: The French Expressionist (BearManor Media, 2014; originally published by The Scarecrow Press, 1987)