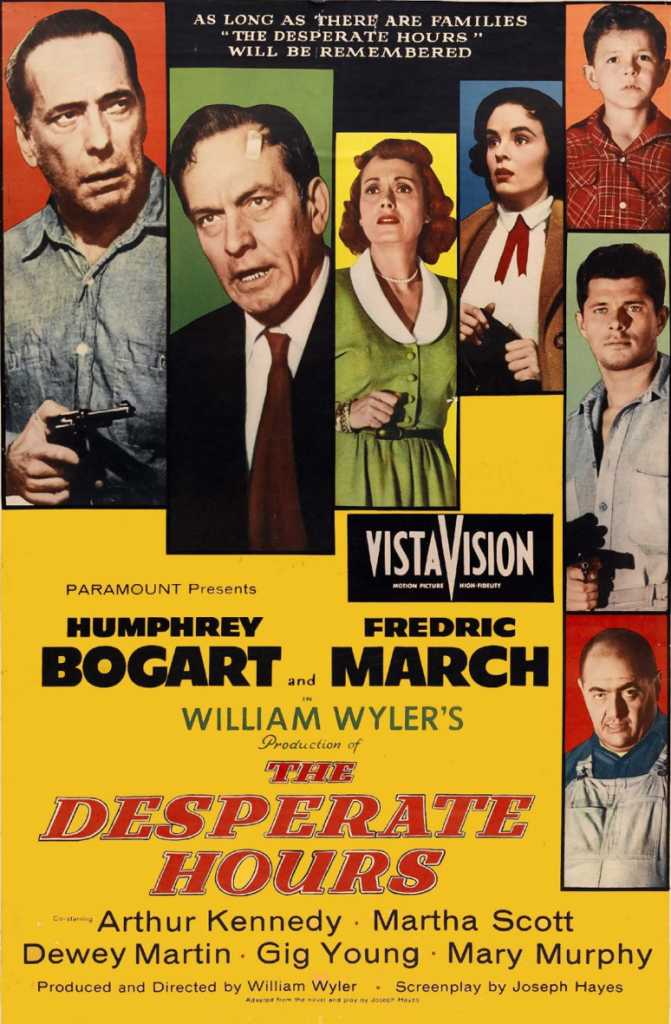

The Desperate Hours

Main Credits

Director: William Wyler. Screenplay: Joseph Hayes based on his novel and play. Producer: William Wyler. Associate Producer: Robert Wyler. Director of Photography: Lee Garmes. Music: Gail Kubik. Art Directors: Joseph McMillan Johnson [J. McMillan Johnson]. Editor: Robert Swink. Costume Designer: Edith Head. Cast: Humphrey Bogart (Glenn Griffith), Fredric March (Dan C. Hilliard), Arthur Kennedy (Deputy Sheriff Jesse Bard), Martha Scott (Eleanor ‘Ellie’ Hilliard), Dewey Martin (Hal Griffith), Gig Young (Chuck Wright), Mary Murphy (Cindy Hilliard), Richard Eyer (Ralphie Hilliard), Robert Middleton (Sam Kobish), Alan Reed (Detective), Bert Freed (Tom Winston), Ray Collins (Sheriff Masters), Whit Bissell (FBI Agent Carson), Ray Teal (State Police Lt. Fredericks). Locations: Los Angeles, California, USA. Released: Paramount, October 5, 1955. 112 minutes.

From Film Noir: The Encyclopedia

Plot Summary

Three escaped convicts take over a middle class home. Glenn is a killer; Hal is his younger brother; and Kobish is a simple-minded psychopath. Confounding their expectations, they meet resistance from the hostages: Dan and Ellie Hilliard, Cindy, their 19-year old daughter, and Ralph, their adolescent son. While they wait for a woman to bring them money, the fugitives fall out among themselves. Hal gets impatient and leaves. Glenn lends Kobish his pistol. Because Kobish won’t give it back, Glenn is unarmed. The police kill Hal and, finding his gun is registered to Dan, they learn the Hilliard’s street address. The woman is stopped for a routine traffic violation, so Glenn tells her to mail the money. Dan goes downtown to pick up the envelope and on his return he sees police have surrounded his house. Dan takes a gun from the police, unloads the bullets and allows Glenn to discover it. Kobish, never loyal to Glenn, unsuccessfully makes a play for the money. Dan tricks Kobish and gets the pistol, which he hides from Glenn. Kobish runs outside and is mowed down. Glenn tries to shoot the gun he took from Dan, but nothing happens. Dan, holding the loaded pistol, tells Glenn that Hal is “full of police bullets, and you did it!” Glenn steps outside and hurls the empty gun at the cops to provoke them to finish him off.

Commentary

After a killer invades a place and takes hostages, he waits for someone or something, especially money. When he waits for a person, the woman or man never arrives, whether to the diner in the desert in The Petrified Forest (1936), the lakeshore cottage in Blind Alley (1939) and its close remake The Dark Past (1948), the train station in Suddenly (1954), or the Hilliard’s home in The Desperate Hours. While he waits for money, the police locate him, as in The Night Holds Terror (1955) and The Desperate Hours. In Escape in the Desert (1945), a loose remake of The Petrified Forest, the invader is a Nazi. At a diner in the middle of nowhere, he waits for a shipment of gasoline so that he can fill up the tank of his getaway car.

Right after the invasion, the killer is in complete control over everyone else. His commitment to waiting, however, leads to his loss of control and his capture or death. As a rule, the police defeat the killer, either attacking him from the outside or tricking him from the inside, as in Suddenly, in which two of the hostages are the town sheriff and a retired secret service agent.

The Desperate Hours is significantly different. Not only does every Hilliard resist Glenn from the outset, but Hal and Kobish also turn against him. Furthermore, Dan, not the police, takes Glenn down. Twenty years before, in The Petrified Forest, Humphrey Bogart began his film career as Duke Mantee, who keeps everyone in line. In The Desperate Hours, Bogart’s penultimate screen character can’t keep anyone in line.

Glenn’s downfall is even dramatized visually, via deep focus shots in three phone calls to the house. The first shot is low from the first floor looking up toward the second floor hallway. Cindy, with a phone, and Glenn, with a gun, are in the foreground to the left. Ellie is mid-distance at the bottom of the stairs. Hal (who is listening in on another phone), Dan and Ralph are small figures standing behind the second floor banister. This is after the invasion. Glenn has control over the Hilliard family.

The second shot is almost the reverse of the first. It is above Dan on the second floor looking down to the first floor. Dan is holding a phone. Cindy and Ellie stand at the end of the railing. Glenn is now a small figure, downstairs in the left corner of the frame, holding the other phone. Although Glenn doesn’t know it yet, the police have killed Hal. Glenn’s time is running out.

The third shot is head high on the second floor. On the right, Cindy is holding a phone, and Korbish is pointing a gun at her. Ellie, first seen at the end of the railing, steps forward in front of Cindy to face Kobish. Glenn is barely visible downstairs. He is holding the other phone, framed inside two pickets of the upstairs railing. The police have traced the gun they found on Hal back to its owner, Dan, and they have surrounded the Hilliard’s house. Glenn’s time is up.

Glenn and Dan are doppelgangers in three ways. First, they’re similar in age. (This is specific to the film. Bogart and March were in their late fifties. In the novel and the play, Dan is in his forties, and Glenn is in his twenties.) Second, Glenn makes Dan become like himself, a man willing to kill. When Dan points a loaded gun at him, Glenn says, “You ain’t got it in you, Pop.” Dan retorts, “I got it in me! You put it there.” Third, each confronts opposition to his authority from the younger generation.

Glenn assumes Hal wants Cindy for her body. In fact, Hal wants her respect. He protests whenever Glenn treats “the Spitfire” as a sex object. But Hal gets nowhere with Cindy, and it hurts. When he asks her in friendly way, “What time’s the next news,” she looks at him with contempt. She walks away and he looks down, humiliated. After observing the middle class world of the Hilliard family, as well as, through the living room curtain, a group of well-dressed teenagers across the street singing in a convertible, Hal recognizes his alienation from them as a class difference.

Glenn brags about all that he’s “learned” his brother, but Hal complains, “You taught me everything, except how to live in a house like this.” That remark cuts Glenn to the quick because he disdains people like Dan. In one of several outbursts in which he smears Dan and his class, Glenn shouts, “Guys like you. Smart-eyed, respectable! Suckers! We seen ‘em, ain’t we Kobish? Sittin’ on parole boards. ‘Throw ‘em back in the cell! They ain’t fit to live with decent folk!’” Hal, however, doesn’t share Glenn’s class anger. He infuriates Glenn by calling Dan, “Mr. Hilliard.” Also, Hal, like Kobish, refuses to give up his gun when Glenn asks him for it.

The conflicts among the gangsters, and Glenn’s failure to overcome them, make The Desperate Hours more noir than the struggles between the gang and the family. Furthermore, tensions within the family dilute the noir in the film because Dan’s confrontation with the younger generation is the stuff of a family melodrama.

In the first scene Dan and Ellie get an earful. Their son wants to be called Ralph instead of “Ralphy,” and he wants to shake his father’s hand good-bye instead of kissing his cheek.

Dan doesn’t want Cindy to marry her boyfriend, Chuck, because “she’s still a child.” Showing off her breasts in front of a mirror, she counters, “Even though she doesn’t look like a child!”

After the invasion, Ralph thinks his father is afraid of the gangsters. Dan must prove to Ralph he knows what he is doing (that father knows best).

His triumph comes when he commands Ralph to run to him and the boy does, even though Glenn has a gun against the boy’s head. (Dan has already allowed Glenn to take away that gun from him because he knows it has no bullets. Hidden from Glenn, Dan has the loaded pistol he cleverly took away from Kobish, just before the police killed Kobish.)

As Hal is a rebel to Glenn, so is Chuck to Dan. Chuck drives a fancy Nash-Healey two-seater sports car, but to Dan it is a “hot-rod.” Dan sees Chuck, an attorney in a black overcoat, as if he were a JD or another Hal in a black leather jacket.

Concomitant with 1950s anti-communist paranoia, all kinds of Hollywood invaders – gangsters, juvenile delinquents, “redskins,” and red planet monsters – are vanquished and “decent folk” regain their security. With Glenn and Kobish lying bullet-ridden on the Hilliard’s front lawn, the final scene can be associated with a rollback of evil by the middle class. Ellie, Cindy and Ralph hug Dan outside their home (Ralph also kisses his cheek), and they walk together through the front door.

Chuck, seemingly the outsider if not the outcast, is left alone in the yard, facing the closed door with his back to the camera. However, the final shot shows that completing the family melodrama means bridging the generation gap. Dan steps back through the doorway and, with a broad smile, waves Chuck to come inside. Chuck romps up the brick steps into the house.

Glenn starts as the unrivaled authority over his henchmen and hostages; he ends unable to dominate anyone. Dan starts as a declining patriarch to his children; he ends with their admiration and obedience. As with the best noir in the classic period, Glenn suffers a nightmare of everything going wrong. Consistent with a 1950s family melodrama, Dan masters a crisis, one that is exacerbated by the external complications from the invasion. The final scene appropriately ends the film noir (with corpses) and the family melodrama (with reconciliation).

Addendum A

It would be interesting to know whether Joseph Hayes – the author of The Desperate Hours as a novel, a Broadway play and a Hollywood script – was familiar with an earlier play, Queen’s Local, by Albert Duffy and Marian Grant, or the 1938 Paramount film based on the play, Hunted Men, scripted by William R. Lipman and Horace McCoy.

In the movie, Joe Albany (Lloyd Nolan) is a racketeer who hides out in a suburban family’s house after he commits a murder. The father, Peter Harris (Lynne Overman), and the mother, Mary (Dorothy Peterson), understand they are hostages. However, their children have no idea about the identity of the man who came home with their father one night, moved in, and now never leaves the house.

Like the Hilliard family in The Desperate Hours, there is a young boy, Robert/”Butch” (Delmar Watson) who idolizes Albany, and a teenage daughter, Jane (Mary Carlisle), who falls in love with him, although she has a fiancé. Unlike other invasion films, Albany is alone. His gang has settled in across the street in an empty house. Also, Albany doesn’t lose control, but he changes under the influence of Butch and Jane. After he flirts with Jane and she tells him how she feels, he rebuffs her. It hurts her, but it makes her realize that her boyfriend, Frank (Johnny Downs), is right for her. When Butch asks him what he knows about “Joe Albany,” he says that the man had chances when he was Butch’s age and he didn’t take them. The way “Joe Albany” turned out is no one’s fault but his own.

In the climax, the police, having discovered Albany’s location, surround the Harris’s house. Inside with the family, Albany draws a gun, revealing himself to Butch and Jane. Butch, crestfallen, walks up to Albany and says it had been a mistake to make him a junior G-man. The boy reaches up and unpins a badge from Albany’s shirt. Then he goes to the stairway, sits down and cries. Peter, who met Albany when he was out on the town and soused (and, therefore, an irresponsible husband and father), now acts as a patriarch should: he tells Albany to hand him the weapon.

The conclusion foreshadows that of The Desperate Hours. Joe Albany, unarmed, walks out of the house toward the police. He wants them to shoot him, so he puts his hand inside his coat — as if he were reaching for a gun. The cops fire, and Albany falls onto the front yard and dies.

Did Joseph Hayes commit some plagiarism?

Hunted Men was directed by Louis King, produced by Harold Hurley, with cinematography by Victor Milner. It isn’t a film noir.

Addendum B

Joseph Hayes had three written works entitled The Desperate Hours (novel, Broadway play and Hollywood script), each of which was about how the “Hilliard” family dealt with a home invasion. Hayes’s fiction was influenced by a real-life event, involving a family named Hill.

According to Wikipedia:

“James Hill and his wife lived in Whitemarsh Township, Pennsylvania, with their five children in 1952, when they were taken hostage in their own house by three escaped convicts. During the ordeal, the family members were treated with dignity by the hostage-takers. The family members were held hostage for 19 hours. The three criminals were apprehended after leaving the Hills’ home, and the incident received significant media attention. Mrs. Hill did not appreciate the media focus, and the family relocated to Connecticut in order to seek out a lifestyle out of the limelight.

Joseph Hayes wrote a novel published in 1953 called The Desperate Hours, which was influenced by the Hill family’s ordeal. The novel by Hayes went on to become a bestseller. In 1954, the Broadway theatre production of the play The Desperate Hours debuted, which depicted a hostage incident similar to that experienced by the Hill family. However, in The Desperate Hours, the scenario was changed from the Hill’s actual experiences, to a fictional portrayal of a family victimized by threats of sexual abuse and other violent acts. The setting for the play was Indianapolis, Indiana.

Life magazine published an article on the debut of The Desperate Hours on Broadway, and included pictures of the actors in the prior residence of the Hills in the Whitemarsh suburb of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In the article, The Desperate Hours was characterized as a “reenactment” of the ordeal experienced by the Hill family. The Life magazine piece wrote that the photographed actors from the play were pictured in “the actual house where the Hills were besieged”. Mrs. Hill experienced a mental breakdown after the piece was published, and James Hill stated he was unable to comprehend why the magazine did not fact check the article through communication with the family.

James Hill filed suit in New York against the magazine’s publisher, Time, Inc. The suit asserted Life had violated privacy law in the state, by conflating the Hill family with fictional events which had not actually occurred. The legal argument drew upon the notion of false light as related to privacy law. After an initial ruling against Life magazine, the New York Supreme Court, Appellate Division remanded the case for a new trial. After litigation through the court system in New York, a decision was found in favor of the plaintiff, with damages awarded of US$30,000.

Time, Inc. appealed the matter to the U.S. Supreme Court, which heard the case in 1966. The Hill family position was argued by Richard Nixon, who was then in private practice.

For the complete post on Wikipedia about this Supreme Court case, regarding issues of privacy in balance with the First Amendment to the US Constitution and principles of freedom of speech, see Time, Inc. v. Hill.