The Missing PI in Film Noir

Introduction

In the page The Film Noir PI: Made in the ’70s, I note that other authors, beside myself, have said that the private eye is not featured in most film noirs in the classic period.

I present the evidence below.

Presentation

Under the “noir type” category, Private Eye, Michael F. Keaney, in his Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959 (McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003), cites the following 16 films. (490)

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Murder, My Sweet (1944)

The Falcon in San Francisco (1945)

The Spider (1945)

The Big Sleep (1946)

The Dark Corner (1946)

Blackmail (1947)

The Brasher Doubloon (1947)

High Tide (1947)

Lady in the Lake (1947)

Philo Vance’s Gamble (1947)

Riff-Raff (1947)

I Love Trouble (1948)

I, the Jury (1953)

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

My Gun Is Quick (1957)

As I explain in the Addendum on the page, The Not Hardboiled PI in Film Noir, there are two private detectives in The Dark Corner. I count both of them.

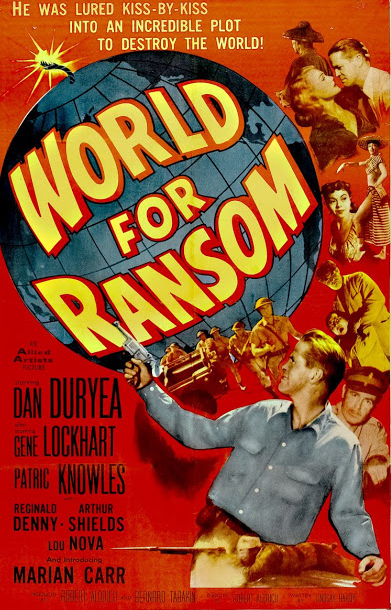

Andrew Spicer, under the entry, Private Eyes, in his Historical Dictionary of Film Noir (The Scarecrow Press, 2010), cites all of the above films except The Falcon in San Francisco. He also adds Out of the Past (1947) and World for Ransom (1954). (247)

Keaney includes both of these films in his book. However, he associates Out of the Past with the noir type Femme Fatale, and, after noting that World for Ransom has “an Irish P.I.,” he associates it with the noir type Far East.

At the end of Historical Dictionary of Film Noir, in Spicer’s filmography of “American ‘Classic’ Noir: 1940-1959,” he has five more: Grand Central Murder (1942), in which a private detective out-sleuths a police detective; Time to Kill (1942), which features the well-known PI Michael Shayne (in a film re-made as The Brasher Doubloon, with Philip Marlowe as the gumshoe); Quiet Please, Murder (1942), which I describe and analyze on the page Quiet Please, Murder; The Last Crooked Mile (1946); and The Mysterious Mr. Valentine (1946).

Spencer Selby, in The Worldwide Film Noir Tradition (Sink Press, 2013), also includes The Last Crooked Mile and The Mysterious Mr. Valentine. Furthermore, he cites the following 12 additional film noirs, identifying each one in his brief plot summary as having a detective who is not on a police force. By year of release, they are: The Tiger Woman (1945), Accomplice (1946), Mysterious Intruder (1946), Half Past Midnight (1948), The Return of the Whistler (1948), The Walking Hills (1949), Guilty Bystander (1950), Danger Zone (1951), The Fat Man (1951), Pier 23 (1951), Roaring City (1951), and Girl on the Run (1958).

In alphabetical order, these six films are in Spicer’s filmography: Accomplice, Danger Zone, The Fat Man, Guilty Bystander, Mysterious Intruder, The Walking Hills. Note that Spicer doesn’t cite any of them as a private eye noir.

Four of the films are in Keaney’s book. However, Keaney doesn’t associate any of them with the noir type Private Eye. The titles and their associated noir types are as follows: Accomplice (Missing Person), Danger Zone (Whodunit), Guilty Bystander (Boozer), and The Return of the Whistler (Missing Person).

In Keaney’s list of Private Eye film noirs, he doesn’t include Behind Locked Doors (1948), although he begins his write-up as follows: “This is an enjoyable little noir about a private investigator hired by an ambitious reporter to infiltrate La Siesta Sanitarium, an insane asylum.” Instead, Keaney classifies it under the noir type Asylum. He also includes My Favorite Brunette (1947) under the noir type Comedy. He says, “Wannabe detective [Bob] Hope is playing P.I….”

Both Spicer and Selby include Behind Locked Doors, but Selby misstates the plot: “Reporter has himself committed to suspicious asylum….” Spicer names My Favorite Brunette, too.

Keaney mentions there is “a portly, Bible-quoting PI” in Born to Kill (1948), whose film noir type he calls “Psycho.” (Spicer and Selby also cite the film.) However, this gumshoe is atypical because he is so dishonest. His client is the best friend of a murdered woman, but he is willing to sell out if he can get more money from the lover (sister-in-law!) of the man he is gathering evidence against.

The number of film noirs in each of these three books is enormous, although their respective filmographies are not at all uniform.

The subtitle of Michael Keaney’s volume says, “745 Films of the Classic Era.”

Spencer Selby has 796 films.

In Andrew Spicer’s filmography, there are eight films for which he gives two titles, such as “Gangs Inc. (aka Paper Bullets).” By counting those films only once, his total is also 796.

According to the titles I have provided above, there are merely 38 private eye film noirs in these books. Yet this number is too high because only half of Selby’s twelve additional films should be counted. Reviewing them below, one by one in alphabetical order, I explain why each of them cannot be included in the list.

Finally, to this total of 32 private eyes in film noirs during the “classic era” (which includes the two in The Dark Corner), I must add Sherlock Holmes and the Voice of Terror (1942), which is not cited in any of these three books. For a description and analysis, see the page Sherlock Holmes-The Voice of Terror.

Not Private Eye Film Noirs

Danger Zone, Pier 23 and Roaring City all feature Dennis O’Brien (Hugh Beaumont), who is, in Selby’s description, a “freelance detective.” That is, he isn’t a private detective for hire.

O’Brien has no clients. He simply gets caught up in mysteries, which he helps solve. The dialog is hardboiled, but it is embarrassingly clichéd. There is no noir visual style. In any event, the chief reason for disputing the inclusion of these titles in a list of private eye film noirs is that they can hardly be considered films. All of them have two half-hour segments, with distinctly different plots and characters. Each segment is television-ready.

Girl on the Run isn’t a U.S. movie, so it seems implausible to include it in a list of American private eye film noirs. It was only first seen in the U.S. on television.

According to Wikipedia, “Girl on the Run is a 1958 private detective film starring Efrem Zimbalist, Jr., Erin O’Brien and Edd Byrnes. The film is in truth, although not legal fact, based on characters and situations created by writer Roy Huggins in a series of 1940s novels and novellas. The picture was directed by Richard L. Bare and aired on ABC as the pilot for 77 Sunset Strip after an initial, brief theatrical release in the Caribbean. This trip to the Caribbean was legally significant. Huggins’ claim to the characters and situations of 77 Sunset Strip was strong, since he had created them in a series of 1940s novels and novellas. But his relationship to this, the first episode of the upcoming series, was comparatively weaker. Marion Hargrove, and not Huggins, had written the script and called it Girl on the Run. Since he had been writing under an episodic television contract, Hargrove had no rights to the series whatsoever. By releasing the project theatrically under the episode title, Warner emphasized Hargrove’s contribution at Huggins’ expense. When it was thereafter aired on television, it was not legally the debut of a new series, but the television premiere of a theatrical film. This made it possible for Warner to argue that the resulting television series was based on the film, which he wholly owned, rather than Huggins’ literary work.”

Half Past Midnight features a lady’s man and adventurer, Kent Taylor (Wade Hampton), who offers to help Sally Ferris (Peggy Knudsen), a woman accused of murder. He isn’t a private eye, and she doesn’t hire him.

However, there is a puzzle for him to solve: who killed the woman who was blackmailing Sally? Since Kent isn’t a real PI, perhaps it is to be expected that he doesn’t solve the mystery. Late in the film he accuses Sally of being the murderer, even though she vehemently denies it. When a homicide detective (Walter Sande) is about to pinch Sally, she begs Kent to believe she is innocent. Kent slugs the detective. A police lieutenant (Joe Sawyer), who has been at odds both with Kent and the detective throughout the film, figures out who the real killer is. He is, of course, the same man Sally had insisted to Kent was the murderer. Kent apologizes to Sally for having doubted her, and they kiss. The film ends with the one-time Casanova getting a steady sweetheart.

The Walking Hills is strong cinema, with a private detective. But it isn’t a private eye film noir.

It takes forty-minutes of running time until we learn, in a flashback, that Shep Wilson (William Bishop) accidentally killed a man and then fled the scene. After the police gave up looking for Shep, the dead man’s father hired a private eye, Frazee (John Ireland), to find him. The film begins with Frazee having caught up with Shep. However, before Frazee reveals himself to Shep, both of them join a larger group of men who ride horses into a desert to dig for $5 million in gold bars that were supposedly buried with a wagon train under sand dunes in the mid-nineteenth century.

Frazee isn’t a private eye in the Sam Spade/Philip Marlowe tradition. He is the most despicable (and greediest) member of the group, even going so far as to threaten to shoot dead anyone who tries to leave when a massive sandstorm approaches them. Furthermore, unlike the “central figure” PI in any actual film noir (with one exception), he is killed, and with his own handgun no less.

The exception is Mysterious Intruder, the fifth entry of eight in The Whistler film series. It ends with the familiar Whistler voice-over. “And so, after balancing precariously on the border line of the law, [PI] Don Gale [Richard Dix] at the end was trying to do the right thing. But he made one fatal mistake. Thinking that one of the killers had come back to attack him, he fired blindly. [Police detectives] Taggart and Burns [Barton McLane and Charles Lane] will never know that Gale’s shots were not meant for them.”

In another film noir, Out of the Past, Jeff Bailey (Robert Mitchum) dies at the end, but it has been a long time since he was a private eye.

In The Falcon’s Brother, George Sanders, who initiated the Falcon character, dies and his actual brother, Tom Conway, takes over the role for more entries in the series. The Falcon’s Brother, however, isn’t a film noir.

Addendum

One of the Appendices in Robert Gerald Porfirio’s unpublished Ph. D. dissertation is, “Film Noirs Listed According to Thematic Categories.” One of the lists is, “Private Eye,” which includes the following 17 films: The Big Sleep, The Blue Dahlia, The Brasher Doubloon, Chicago Deadline, Cornered, Cry Danger, The Dark Corner, Dead Reckoning, The Glass Key, Guilty Bystander, Johnny Angel, Johnny O’Clock, Kiss Me Deadly, Lady in the Lake, The Maltese Falcon, Murder, My Sweet, and Out of the Past. (The Dark Age of American Film: A Study of the American Film Noir [1940-1960], Yale University, Volume II, 254)

Porfirio provides no new private eye film noirs to add to the list I compiled above. This is because all of his films that aren’t already present in my list lack a bona fide private detective.

The Blue Dahlia (1946): a veteran

Chicago Deadline (1949): a reporter

Cornered (1945): a Canadian pilot, ex-prisoner of war

Cry Danger (1951): an ex-convict, innocent of the crime

Dead Reckoning (1947): an Army captain

The Glass Key (1942): a politician’s bodyguard

Johnny Angel (1945): a ship captain

Johnny O’Clock (1947): a co-owner of a casino

It isn’t legitimate to name a film noir as a “private eye” film noir simply because the central character investigates a crime, even if that character is a private civilian (i.e., someone who isn’t on a police force).

If it were legitimate, then the film noirs I call “war noirs” would have to be included. In each of them, there is a man falsely accused of murder. Either by himself, or with a working woman, or (if he has been jailed by the police) by the efforts of the woman alone, an investigation is made that ultimately clears his name.

None of these film noirs has ever been cited as a private eye film noir. They are, in alphabetical order: Double Alibi, Framed, Stranger on the Third Floor, I Wake Up Screaming, Man Hunt, Meet Boston Blackie, Pacific Blackout, Rage in Heaven, All Through the Night, Fly-By-Night, Little Tokyo, U.S.A., Saboteur, Street of Chance, This Gun for Hire, A Tragedy at Midnight, The Gorilla Man, Hangmen Also Die!, Journey Into Fear, Two Tickets to London, The Conspirators, Ministry of Fear, Phantom Lady, When Strangers Marry.

They were all released between 1940 and 1944. (For more information about these “war noirs,” see the page Film Noir Plot Elements: WWII vs. Postwar.)

Two additional film noirs, Two O’Clock Courage and Spellbound, which were both released in 1945, share the plot elements of the earlier war noirs. (See the page Two O’Clock Courage for more analysis of this film.)

If the category, “private eye film noir,” is to have any value, then the films in the list have to feature an actual private detective, not simply a private civilian investigator. This is especially important because, by strictly – and legitimately – compiling an accurate list, the slender number of private eye film noirs is more glaringly – and justly – exposed.

A central tenet of the film noir hardboiled paradigm is that the private eye has iconic status (and much other lofty significance). Because the PI, in fact, is very rarely a “central figure” in film noir, this tenet for exponents of the hardboiled paradigm can be rightly understood, at least by non-believers of the paradigm, as a myth, a falsehood.