The Unfaithful

Introduction

Below is a transcript of my presentation that preceded a screening of The Unfaithful at the Pacific Film Archive (PFA), the University of California, Berkeley, on August 1, 2008. I am grateful to Michael Guillen for posting it on the Internet.

The post omits the books that I named, which are cited below, and a reference to a handout. The information in the handout is now provided in the following two separate pages: Published Sources: Women’s Noirs and Published Sources: Men’s Noirs.

Following the transcript, I provide my Plot Summary and Commentary (plus the excised final paragraph) that was published in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia.

Main Credits

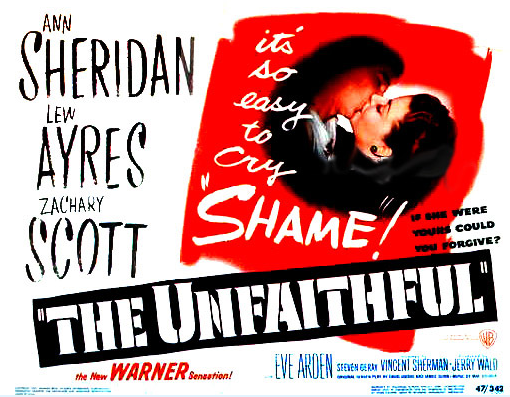

Director: Vincent Sherman. Screenplay: David Goodis, James Gunn based on the novel by W. Somerset Maugham (uncredited). Producer: Jerry Wald. Executive Producer: Jack L. Warner. Director of Photography: Ernest Haller. Music: Max Steiner. Art Director: Leo K. Kuter. Editor: Alan Crosland, Jr. Cast: Ann Sheridan (Chris Hunter), Lew Ayres (Larry Hannaford), Zachary Scott (Bob Hunter), Eve Arden (Paula), Jerome Cowan (Prosecuting Attorney), Steven Geray (Martin Barrow), John Hoyt (Det. Lt. Reynolds), Peggy Knudsen (Claire), Marta Mitrovich (Mrs. Tanner), Douglas Kennedy (Roger), Claire Meade (Martha), Frances Morris (Agnes), Jane Harker (Joan). Locations: Angel’s Flight Railway, Bunker Hill, Downtown, Los Angeles, California, USA. Completed: ?. Released: Warner Bros., June 5, 1947. 109 minutes.

Presentation at the Pacific Film Achieves, Berkeley, CA (August 1, 2008)

PFA curator Steve Seid reiterated that David Goodis — in the wake of the 1947 film adaptation of his novel Dark Passage — quickly secured a contract as a studio writer in Hollywood. However, he had a rapid downfall and by the 1950s he had moved back to Philadelphia. “The irony is that you can see in a single double-bill the entire output from his time in Los Angeles,” Seid quipped. Other filmic adaptations like Jacques Tourneur’s Nightfall eventually led Goodis’s work back to Hollywood, but not the author himself.

Seid then introduced Dan Hodges, whose work will be included in the forthcoming 4th Edition of Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style [published as Film Noir: The Encyclopedia, Overlook Duckworth, 2010].

Hodges remarked on Vincent Sherman’s The Unfaithful (1947) by reading prepared notes:

“The wind stepped through the window and sat next to me.”

David Goodis didn’t write that, but a characteristic of his style was to describe something inanimate behaving as if it were alive. In The Unfaithful, there’s a splendid example of this in a sentence spoken by Eve Arden, “I moved here to get away from trouble, but it followed me right up in the elevator.”

Once you see The Unfaithful, I urge you to watch The Letter, directed by William Wyler and starring Bette Davis, released in 1940. The Unfaithful shares similarities with The Letter, but the contrasts are more striking. For example, I find Ann Sheridan is in a more noir situation than Bette Davis, because her plight is more undeserving. Also, in The Letter, the society in the south Pacific rubber plantations, as represented by marriages, is very cohesive. But in The Unfaithful, society – in terms of marriage – is unstable, splintering. So it is more noir.

In The Unfaithful – and here it’s also different from The Letter – Ann Sheridan is a woman in distress who is unique in film noir. She’s not threatened with losing her sanity (like Ingrid Bergman in Gaslight) or with losing her life (like Bergman in Notorious). She may lose her husband. Her marriage may fail, like everyone else’s.

Both The Unfaithful and The Letter are notable examples of the kind of film noir that challenges the standard academic as well as popular description of film noir. For decades, the terms and concepts that have been most frequently used to define film noir have not, in fact, been applicable to many, many movies that are included in the various film noir encyclopedias.

[Show the audience books that include many film noirs that are women’s noirs, as well as hardboiled noirs, by Robert Ottoson (The American Film Noir), Specer Selby (Dark City: The Film Noir), Michael L. Stephens (Film Noir: A Comprehensive, Illustrated Reference Guide to Movies, Terms and Persons), and Michael F. Keaney (Film Noir Guide: 745 Films of the Classic Era, 1940-1959).]

The film noirs that have gotten short shrift are “women’s pictures,” which are likely to take place in a home and deal with a romantic crisis (so-called “tear-jerkers,” “three hankies” or “weepies”). However, during the classic years of film noir, especially in the 1940s (less so in the 1950s), many women’s pictures are crime movies that have the characteristics of the noir visual style.

[Show the audience books that exclusively promote the hardboiled paradigm by Foster Hirsch (Film Noir: The Dark Side of the Screen), Bruce Crowther (Film Noir: Reflections in a Dark Mirror), Eddie Muller (Dark City: The Lost World of Film Noir), and Sheri Chinen Biesen (Blackout: World War II and the Origins of Film Noir).]

Women’s noirs have been ignored because the mass media and academic descriptions of film noir only deal with the “hardboiled.” As a result, film noir is reduced to these kinds of essentials:

• the protagonist is male (such as an investigator, a criminal, a victim of circumstance)

• the literary source is hardboiled crime fiction

• there is brutal violence (by fists and guns)

• the time and place is a contemporary U.S. city (and not, say, Victorian London or a family’s home)

This standard view of film noir ignores the published stories, novels and plays that primarily addressed a female audience and were adapted into film noirs. The Letter is based on a novel by W. Somerset Maugham.

By my count these published sources of women’s noirs nearly equal all published works aimed at a male audience. But not all men’s noirs are based on hardboiled short stories or hardboiled novels. Despite the focus on hardboiled literature, there are more women’s noirs based on published works aimed at women than men’s noirs based on hardboiled published sources.

Furthermore, of course, there were original screenplays written for women’s noirs, such as for The Unfaithful.

The standard view of film noir lavishes attention on the femme fatale and ignores the woman in distress. (Updated in July 2024.) There is no book about the woman in distress in film noir. There is no chapter about the woman in distress in books that have chapters on not only about the femme fatale but also about the private detective, even though there are precious few film noirs with a private eye. (See the page The Missing PI in Film Noir and as well as related pages about the private detective in film noir on this website.)

The term woman in distress isn’t even mentioned in books much less articles; instead there’s the rare reference to one of two — dictionary proven — inappropriate terms, woman in jeopardy or woman in peril. (See the page Significance of the Woman in Distress for a demonstration of which of the three terms, according to the dictionary, is the only viable one, i.e., woman in distress.) Furthermore, by my count, more film noirs feature a women in distress than a femme fatale. (See the page Woman in Distress vs. Femme Fatale.)

It is critical to assess the full range of film noirs that were released between 1940 and 1959 if we want to understand the full range of political and social issues that film noir addresses. For example, take women’s sexuality.

With the femme fatale, we talk about the threat to the man right then and there in the story. And we relate that to men returning from WWII who were confronted with women who had become more economically independent through their jobs during the war and more sexually – what? independent, aggressive…

But women’s noirs raise issues about women’s sexuality that are at least as interesting as those related to femme fatales and their male victims in hardboiled noirs.

For example, the plot in The Unfaithful has a lot more to do with tension between the sexes in the post-war years — because of issues about sex — than just about any men’s noir.

Finally, until women’s film noirs are properly recognized, a comprehensive history and balanced analysis of film noir will be, by definition, impossible.

Addendum: Plot Summary and (Full) Commentary in Film Noir: The Encyclopedia

The following is the text that I submitted to the editors of Film Noir: The Encyclopedia for The Unfaithful. It has been reformatted into shorter paragraphs.

The last paragraph in my commentary wasn’t published. I include it below.

Plot Summary

The night before Bob returns from a business trip, Chris is attacked at home by an intruder, Tanner, and she stabs him to death. The next day she tells Hannaford (a friend who is a divorce lawyer), the police and Bob that she’d never seen the man before. Hannaford learns she’s lying when Barrow, a small-time art dealer, tries to sell for $10,000 a sculpture of Chris’s head, signed by Tanner. Hannaford turns Barrow down and tells Chris. She wants to pay the blackmailer because she doesn’t want Bob to find out she’d had an affair with Tanner during the war. Chris and Hannaford expect Barrow to call her. Instead, Barrow takes the sculpture to Mrs. Tanner and they show it to Bob. Angry at Chris for betraying him, Bob tells her he wants a divorce. Mrs. Tanner wants Chris imprisoned, so she takes the sculpture to the police. Chris is charged with Tanner’s murder. At the trial Hannaford argues to the jury that, although Chris is guilty of infidelity, she killed Tanner in self-defense. Chris is acquitted. Just before she moves out, Hannaford convinces Bob to hang on to his marriage with her.

Commentary

The woman in distress in The Unfaithful is unique in film noir. She is not threatened with losing her sanity (like Gaslight, Possessed and Whirlpool) or her life (like Notorious, Sorry, Wrong Number and Sleep, My Love). But she may lose her husband. During the 1940s, the U.S. divorce rate increased modestly from 2.0 per 1000 to 2.6, much lower than the growth rates after 1970. However, The Unfaithful suggests that stable marriage in postwar America is in jeopardy. When the movie begins, a voice-over intones, “The problem with which it deals belongs not to any one city, town or country but is of our times.”

Women casually (and comically) parade through Hannaford’s law office to file for divorce, not necessarily their first one. Paula, a divorcee and Bob’s cousin, says, “If there’s one person in this town you can trust, it’s Chris.” After Chris’s affair is exposed, the implication is that there are no exceptions. However, the association of the “unfaithful” with Everywoman is challenged later on.

Multiple scenes deal with the social and sexual pressures experienced by women who were married but alone for the duration. Chris tries to get Bob to understand what her long loneliness was like. At the trial, Hannaford says without the war there would have been no affair. Most interestingly, Paula tells Bob he’s not blameless because he rushed Chris into marriage after knowing her just two weeks before he shipped out. “You didn’t want anyone making time with her while you were away, so you hung up a No Trespassing sign, like you’d stake a gold claim.” The film ends with Chris’s infidelity contextualized and forgiven, but this “problem…of our times” continues.

The Unfaithful is supposed to be based on The Letter. There are some similarities: a wife kills a man she’s had an affair with; incriminating evidence exists; and the woman is acquitted. However, the contrasts are striking. The Letter has a strong noir style and an intense score. The Unfaithful lacks the style and background music. The lawyer and the wife of the lover deal with the evidence differently. The affair between the man and the wife is different. After her acquittal, the finale for the woman is different. Amid south Pacific rubber plantations there’s class – and racial – solidarity. In southern California suburbia there’s cattiness and backstabbing. The lawyer in The Letter is happily married. Hannaford is a bachelor. Where marital betrayal is pervasive, by staying single he can’t be made a cuckold. In The Letter one marriage is on the rocks. In The Unfaithful only one marriage may succeed. And if it does, it will be an island on the land of cheating and break-ups. (Although David Goodis shares screenwriting credit with James Gunn for The Unfaithful, there’s one line that could be dropped into any of his novels or stories, when he makes an inanimate object come alive. Comforting Bob, Paula says, “I moved here to get away from trouble, but it followed me right up in the elevator.”)

Postscript: Post-World War II Divorce Rates in the U.S.

In my write-up above for Film Noir: The Encyclopedia, I say, “During the 1940s, the U.S. divorce rate increased modestly from 2.0 per 1000 to 2.6, much lower than the growth rates after 1970.” However, there was a spike in 1946, when the divorce rate reached 4.6 per 1000 marriages. It then declined (i.e., the rate was going down when The Unfaithful was being shot). It is fair to assume that the spike may have influenced the screenplay of The Unfaithful. Furthermore, based on past history, it might have also been assumed by the scriptwriters that the divorce rate would continue to rise. Such an assumption, however, would have been wrong.

In December 1973, The U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare issued the following report 100 Years of Marriage and Divorce Statistics United States, 1867-1967.

Under the topic, “National Divorce Rates,” the document says:

The trend of the divorce rate differs from that of the marriage rate by showing a consistent increase for a period of 80 years, 1867-1946. Although this increase was accelerated by two World Wars and temporarily reversed by the Depression, the trend was resumed as soon as the situation returned to normal. During the 80-year period an annual rate was smaller than that for the preceding year in only seven cases (1913, 1918, 1921, 1922, 1930, 1931, and 1932).

The time trend became completely different after 1946. It could be expected that the extremely inflated post-World War II rates would revert to a more normal size and that the increase would then be resumed. This, however, did not happen. The inflated rate declined from 4.3 in 1946 to 2.3 in 1955 and fluctuated from 2.1 t0 2.3 between 1955 and 1963. A new wave of increases began in 1963, and the rate reached 2.6 in 1967 – a growth of 13 percent in 4 years. The rate was 2.9 per 1,000 for 1968, and it increased to the provisional rate of 4.0 for 1972, so this increase continued after 1967 and lasted much longer than that which occurred during and after World War II. (p. 9)