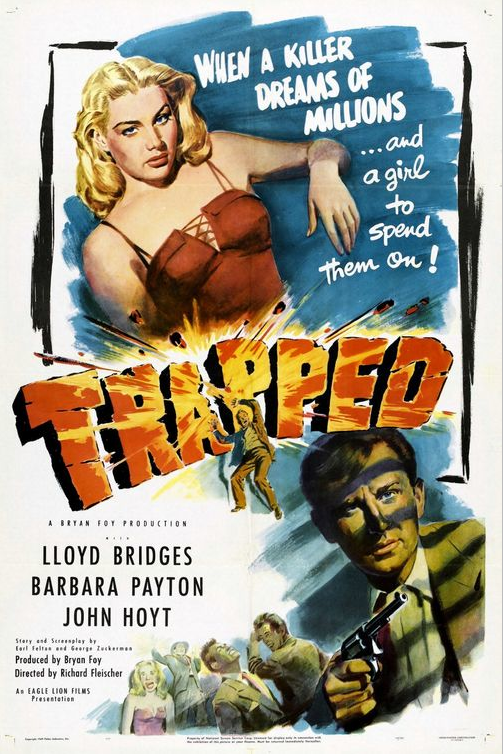

Trapped

Introduction

Trapped was among my assignments for Film Noir: The Encyclopedia (Overlook Duckworth, 2010). Although my plot summary was published, my commentary was replaced by a single paragraph. The credit for both my summary and the different commentary was given to James Ursini, one of the co-editors of the book. Below is my plot summary and my original commentary about Trapped. It has been reformatted into shorter paragraphs.

Main Credits

Director: Richard Fleischer. Screenplay: Earl Fenton and George Zuckerman based on their story. Producer: Bryan Foy. Director of Photography: Guy Roe. Music: Sol Kaplan. Cast: Lloyd Bridges (Tris Stewart), Barbara Payton (Meg Dixon, alias Laurie Fredericks), John Hoyt (Agent John Downey, alias Johnny Hackett), James Todd (Jack Sylvester), Russ Conway (Chief Agent Gunby), Robert Karnes (Agent Fred Foreman). Released: Eagle Lion, October 1, 1949. 78 minutes.

From Film Noir: The Encyclopedia

Plot Summary

Tris is in prison for counterfeiting money. He used plates that almost perfectly duplicate U.S. bills. After he promises Treasury Department agents to help them get the plates, they stage his escape. They also let him think he’s double-crossed them and given them the slip to get back to his girlfriend, Meg. She’s a cigarette girl at a nightclub, where John, pretending to be a well-heeled grifter, is keeping an eye on her. Jack, who now has the plates, offers Tris $250,000 counterfeit for $25,000 real money. John cons Tris into asking him to put up the 25 grand. The sting operation is spoiled, however, when Meg overhears a man at the club say John’s a government agent. Tris tries to kill John and steal the real money, but he fails and is sent back to prison. John goes with Jack to a trolley car barn, where Jack has the counterfeit money and the plates. Meg tries to warn Jack that John’s a T-man, but Jack doesn’t trust her. Jack turns and shoots Meg, giving John a chance to get away. The police arrive and chase Jack among the trolley cars, until he touches a live wire.

Commentary

The foot chase after a criminal by the police, as in the trolley car barn in Trapped, is an important visual motif in film noir. It is an unusual one, however, for several reasons.

First, it is a scene with frequent cuts that juxtapose shots of the hunters and the hunted at extreme angles and screen sizes, from close-ups to long distances. In contrast, consider the noir motifs presented in Alain Silver and James Ursini’s The Noir Style (The Overlook Press, 1999): the femme fatale, the doppelganger, night and the city, and the impact of the dark past or a psychological scar on a noir character. Their noir motifs are depicted either with production stills or enlarged frames.

Second, it happens at the end of the film, and the climax is almost always the death of the criminal, which concludes the story. Other motifs may appear at any time in a film.

Third, it is historically specific to film noirs released during 1948-1950. Other motifs occur throughout the classic period, 1940-1959.

Fourth, it takes place in a particular setting, which is a blue-collar work site or an urban area of working class residence or recreation. Other motifs aren’t defined by or associated with any particular class.

The first of these foot chases is in The Naked City (1948). A killer flees the cops out of New York’s Lower East Side onto the Williamsburg Bridge. Several aspects of this scene recur in later film noirs: a) the criminal climbs to a place high above the police; b) the police are shown below the criminal; and c) when the criminal dies, he falls.

In Trapped Jack climbs onto the roof of a trolley. After he electrocutes himself, he topples off the car.

In Panic in the Streets (1950) the police pursue a plague-carrying murderer through a coffee warehouse on the New Orleans docks. As he tries to escape by climbing up a rope to reach a ship, they shoot him and he falls into the harbor.

In Never Trust a Gambler (1951), the police chase a killer through a warehouse on the Los Angeles waterfront until they are able to rescue his wife, who he had forced to accompany him. Then he climbs up a tall crane used to unload cargo, followed by a homicide detective. From the operator’s cabin, he makes the boom start moving sideways. Leaving the cabin, he heads toward the end of the boom, planning to jump to another crane and escape. As he passes over the detective, unseen on the lower level of the boom, the detective reaches up and pulls the killer’s leg, sending him falling to his death on the dock below. (The film was made in December 1950.)

In Night and the City (1950) a spiv runs through working class neighborhoods and a construction site in London. When he’s slain (by mobsters, not bobbies), he falls into the Thames.

In Follow Me Quietly (1949) a serial killer falls off the catwalks of a refinery after the police fire up at him.

In White Heat (1949) a homicidal gang leader climbs to the top of a Hortonsphere of explosive gas and unloads his gun at it. His “fall” is metaphorical.

In Southside 1-1000 (1950) a secret service agent chases the female “boss” of a counterfeiting ring through a warehouse to a bridge over railroad tracks. When he grabs hold of her, she tries to push him off the bridge. In their struggle she slips out of his grasp and falls in front of an oncoming train.

In Street with No Name (1948) and The Tattooed Stranger (1950) the police kill their quarry after a chase, respectively, in a factory and a granite-works for tombstones.

In Quicksand (1950) and Mystery Street (1950) a criminal is arrested after he runs, respectively, on and below the Santa Monica pier and across a Boston railroad yard.

The hunt to the death is also underground: in the storm drains of Los Angeles (He Walked by Night, 1948) and Vienna (The Third Man, 1949), among hydroelectric generators deep down inside Boulder Dam (711 Ocean Drive, 1950), and beneath Chicago’s railroad terminal and through its municipal tunnel (Union Station, 1950).

Above ground or underground a criminal flees until it is impossible to go farther, and then he is trapped. The foot chase both dramatizes and symbolizes the futility of trying to evade punishment. It is also always a high point of visual style. For example, Trapped is in the first rank among film noirs in quality and pervasiveness of the noir style, yet the scene in the trolley car barn still stands out.

Addendum 1

A British film noir, The Clouded Yellow (1950), ends with a chase scene starting in a huge warehouse at a dock in Liverpool. The murderer chases his female prey high up on the building’s steeply slanted roof, from which he slips and falls in front of an oncoming train.

Addendum 2

As noted above, the time-period of film noirs with “the foot chase after a criminal by the police” that takes place in “a blue-collar work site or an urban area of working class residence or recreation” was as brief as it was specific, 1948-1950.

In 1953, one more film noir was released with a foot chase, which is similar yet different from those that preceded it.

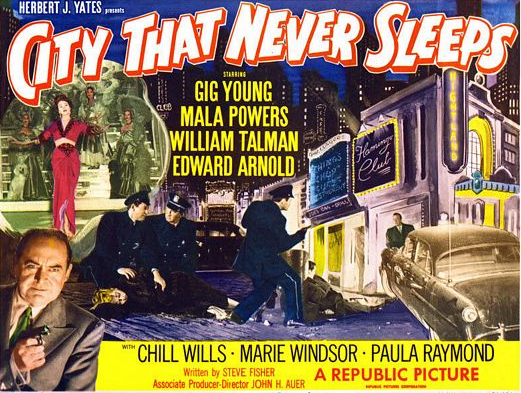

Set in Chicago, in the climax of City That Never Sleeps, a policeman (Gig Young) chases a murderer (William Talman) through an abandoned building, up the stairs of a water tower, across tenement building rooftops, and finally over an elevated streetcar’s rail tracks.

It is a long scene with “the frequent cuts that juxtapose shots of the hunters and the hunted at extreme angles and screen sizes, from close-ups to long distances” characteristic of the foot chases in the film noirs of the previous years.

Standing on a street far below the train tracks, other cops do not fire their guns at the killer but watch as the policeman struggles with him. The fight ends when the criminal grabs the third rail with both of his gloved hands and is electrocuted. The murderer’s dead body slips between the tracks and, typical of the earlier film noirs, the camera points upward to show it falling down to the street.

Unlike the earlier film noirs, City That Never Sleeps does not swiftly end with the criminal’s death. First, the policeman goes to a church to comfort his younger brother, who had been a sidekick of the criminal, because their father, a policeman himself, was killed by the criminal. Next, he goes to his police station where he indicates that he is going to remain on the force, instead of quitting as he had intended at the start of the film. Then he returns to his home street, where his wife (Paula Raymond), whom he was going leave for another woman, is waiting for him. With his commitment to his job and marriage restored and strengthened, the film (finally) ends.

The foot chase in City That Never Sleeps is as visually fine as any in the earlier film noirs. But the death of the criminal does not finish off the plot. Instead, this film noir’s conclusion is both more prolonged and far more sentimental. The key explanation for the ways that the foot chase and the conclusion are so different in this film noir might be attributed to the three-year interval between the end of the time-period for the original foot-chase film noirs and the release of City That Never Sleeps.