Vertigo

This post is my way of celebrating the 60th. anniversary of the release of Vertigo.

Vertigo: An Exemplar of Both the Femme Fatale and the Woman in Distress

I. Main Credits

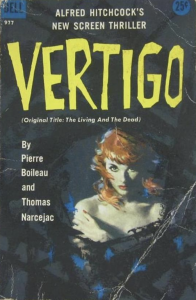

Director: Alfred Hitchcock. Screenplay: Alec Coppel and Samuel A. Taylor, based on the novel, D’Entre Les Morts, by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, with contributing writer Maxwell Anderson (uncredited). Producer: Alfred Hitchcock (uncredited). Associate Producer: Herbert Coleman. Director of Photography: Robert Burks. Music: Bernard Herrmann. Art Directors: Henry Bumstead and Hal Pereira. Editor: George Tomasini. Cast: James Stewart (John “Scottie” Ferguson), Kim Novak (Madeleine Elster/Judy Barton), Barbara Bel Geddes (Midge Wood), Tom Helmore (Gavin Elster), Henry Jones (Coroner), Joanne Genthon (Carlotta Valdes). Released: Paramount Pictures, May 9, 1958. 128 minutes (129 minutes, 1996 restored).

II. From 1972 – 2012 Vertigo rises from unmentioned to #1; in 2022 it slipped to #2

In 2012, Vertigo was ranked the greatest film of all time by Sight and Sound, a monthly film magazine published by the British Film Institute. The results of the Sight and Sound poll for the all-time best films have been released every ten years since 1952. In the first poll, neither the later longstanding #1, Citizen Kane, nor the much later upstart, Vertigo, were included. In 1962, Citizen Kane, from outside of the previous top 10, jumped to #1. In 1972, Citizen Kane retained the top spot, as it also did in 1982, when there was a tie for #7: L’Avventura (#5 in 1972), The Magnificent Ambersons (#8 in 1972) and a new entry, Vertigo. In the 1992 poll Citizen Kane remained #1. However, L’Avventura and The Magnificent Ambersons dropped out of the top ten, and Vertigo rose to #4. In 2002, the polling placed Vertigo second behind Citizen Kane.

In the Sight and Sound poll of 2022, Vertigo slipped to #2, replaced at the top by Jeanne Dielman, 23, Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles, directed by Chantal Akerman of Belgium.

III. The Set-Up of Scottie

The complicated plot of Vertigo can only be sketched here. Nevertheless, the following description isn’t brief because I want to explain how, in the first half, a woman (Madeleine) is one of film noir’s most deceiving femme fatales, whereas, in the second half, this same woman (Judy) is one of film noir’s women in distress suffering the most intense psychological plight.

Vertigo dramatically opens with a man being chased across rooftops in San Francisco by a cop and Scottie Ferguson, a police detective. After jumping to a building with a slanted roof and ceramic tiles, Scottie slips and slides down until he is hanging precariously from a gutter. Each time he looks down into an alley several stories below, what he sees seemingly stretches and recedes farther away. This psychological experience unnerves him.

Vertigo dramatically opens with a man being chased across rooftops in San Francisco by a cop and Scottie Ferguson, a police detective. After jumping to a building with a slanted roof and ceramic tiles, Scottie slips and slides down until he is hanging precariously from a gutter. Each time he looks down into an alley several stories below, what he sees seemingly stretches and recedes farther away. This psychological experience unnerves him.

When the policeman tries to save him by extending a hand and telling him to grab it, Scottie is incapable of letting go of the gutter. The officer loses his footing on the tiles and plunges over Scottie to his death. What is key to this scene, although it is not depicted, and the audience only indirectly learns it later, is that the newspapers report what happened.

Since Scottie isn’t fit to continue working in the streets, and he doesn’t want to sit behind a desk, he quits the police force. Soon afterwards he is contacted by a former college classmate, Gavin Elster. Unknown to the audience for most of the film, Gavin has groomed his gorgeous mistress to be a stand-in for his actual wife, Madeleine, in order to carry out an elaborate murder scheme that will make it appear his wife has committed suicide.

Gavin tells Scottie that he is worried about Madeleine because she blanks out and goes places and does things, then afterwards she can’t remember where she went or what she did. The cause, he suggests, is that a dead person “takes possession” of her.

Gavin asks Scottie to follow Madeleine in her “wanderings” around the city. When Scottie declines, Gavin says he and Madeleine will be at Ernie’s restaurant that night, and there Scottie “can see her.” Once he does, he is hooked, falling into Gavin’s trap. The Madeleine that Scottie sees at Ernie’s, and then trails around San Francisco, isn’t Gavin’s wife; she is his lover and accomplice in the murder plot. A stupendous artifice is now afoot.

Gavin asks Scottie to follow Madeleine in her “wanderings” around the city. When Scottie declines, Gavin says he and Madeleine will be at Ernie’s restaurant that night, and there Scottie “can see her.” Once he does, he is hooked, falling into Gavin’s trap. The Madeleine that Scottie sees at Ernie’s, and then trails around San Francisco, isn’t Gavin’s wife; she is his lover and accomplice in the murder plot. A stupendous artifice is now afoot.

IV. The Nonpareil Duplicitous Femme Fatale

Madeleine not only intends to dupe Scottie that her mind is “taken possession” by her supposed great-grandmother, Carlotta Valdes, who went “mad” and died “by her own hand” in 1857. More importantly, to better manipulate him, she also aims to take possession of his heart. She accomplishes everything. Her conquest of Scottie is sealed when she feigns being in another trance and apparently tries to drown herself by jumping into the San Francisco Bay at Fort Point under the Golden Gate Bridge.

Madeleine not only intends to dupe Scottie that her mind is “taken possession” by her supposed great-grandmother, Carlotta Valdes, who went “mad” and died “by her own hand” in 1857. More importantly, to better manipulate him, she also aims to take possession of his heart. She accomplishes everything. Her conquest of Scottie is sealed when she feigns being in another trance and apparently tries to drown herself by jumping into the San Francisco Bay at Fort Point under the Golden Gate Bridge.

He “saves” her. (In the film’s climax she admits that she is a “wonderful” swimmer.) In his apartment, the audience can infer, if her clothes are hanging up to dry in his kitchen, he has stripped her naked before putting her under the covers of his bed. After she “comes to” from her faked trance, she asks why he didn’t take her home. Since she knows he follows her every day from her building, she also knows he lies when he says he doesn’t know where she lives.

He “saves” her. (In the film’s climax she admits that she is a “wonderful” swimmer.) In his apartment, the audience can infer, if her clothes are hanging up to dry in his kitchen, he has stripped her naked before putting her under the covers of his bed. After she “comes to” from her faked trance, she asks why he didn’t take her home. Since she knows he follows her every day from her building, she also knows he lies when he says he doesn’t know where she lives.

Once he is madly in love with her, she can take advantage of his emotional weakness and get him to believe her stories about her supernatural relationship with Carlotta. Because the audience, like Scottie, is being hoodwinked by Madeleine, her triumph as one of film noir’s most duplicitous femme fatales goes unappreciated. In being a femme fatale, Madeleine is self-conscious that she is “the tool” and Scottie is “the victim of Gavin Elster’s plan to murder his wife.” In the film’s climax Scottie learns Gavin ditched Madeleine after the killing. Nevertheless, what counts in this section of Vertigo is that, until moments before the murder, Madeleine is disciplined in deluding Scottie and executing what Gavin has devised.

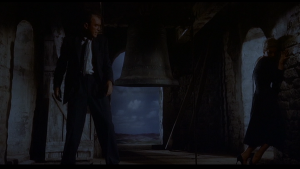

Madeleine tells Scottie that, like Carlotta, she is losing her mind and will soon die. She speaks of a recurring dream, which foretells her death, where there is a place “with a tower and a bell…[that] seems to be in Spain.” (For more about this made-up dream to deceive Scottie, see below: VIII. A Speculation about Scottie’s Nightmare.)

As Gavin has planned, Scottie infers that the place in Madeleine’s dream is the Mission San Juan Bautista. He is sure if she goes there, it will “finish” her dream, “it will destroy it.” They drive to the mission, and they kiss passionately inside a livery stable. Suddenly, she breaks away, saying there is something she “must do.” She runs ahead to the bell tower, and Scottie chases after her. When he looks up at the top of the tower, his expression shows he believes she is going to leap from it to kill herself.

As Gavin has planned, Scottie infers that the place in Madeleine’s dream is the Mission San Juan Bautista. He is sure if she goes there, it will “finish” her dream, “it will destroy it.” They drive to the mission, and they kiss passionately inside a livery stable. Suddenly, she breaks away, saying there is something she “must do.” She runs ahead to the bell tower, and Scottie chases after her. When he looks up at the top of the tower, his expression shows he believes she is going to leap from it to kill herself.

Here occurs the lynchpin of the murder plan. When Gavin solicits Scottie to follow Madeleine, he alludes to what he read “in the newspaper” about the events on the rooftop. Therefore, Gavin knows about Scottie’s ailment, that he suffers from acrophobia (a fear of heights), which gives him vertigo (making him feel dizzy).

Gavin and Madeleine count on Scottie being unable to follow her to the top of the stairs. Once he can’t climb any higher, he won’t see that she doesn’t die. Instead, when she enters the belfry, Gavin, who is already there, throws his wife’s corpse, wearing the same gray suit as Madeleine, off the tower. Since Scottie believes Madeleine was alone, a coroner’s inquest can only reach the verdict that she “committed suicide while of unsound mind.”

The night after the inquest Scottie has a nightmare from which he suffers a mental breakdown. He is institutionalized for a year. On a visit to see Scottie, Midge tells his doctor that the trauma was caused by his being in love with a woman whose death he feels responsible for. As a femme fatale, Madeleine doesn’t make Scottie lose his life, but she is responsible for his losing his mind.

V. The Nonpareil Woman in (Psychological) Distress

Even after Scottie’s official recovery a year later, his obsession with Madeleine continues. When he goes to the Podesta Baldocchi flower store, where he watched Madeleine buy a nosegay, such as Carlotta wore in the painting at the Legion of Honor art museum, his attention is suddenly captured by a young woman walking by. He follows her to her apartment, where he learns her name is Judy Barton. She puts on the perfect act that she is no one he knows. (Everything about Judy is different from Madeleine, such as her accent, her makeup, her hair style, and hair color.)

When she agrees to have dinner with him, he lets her have an hour “to change and get fixed up.” As soon as he is gone, she has a flashback to the bell tower, which reveals to the audience her complicity in the murder. At first, she intends to pack a suitcase and run away, after writing him a letter that confesses her participation in Gavin’s plan and, what was not part of the plan, falling in love with him. (Recall their passionate kiss in the livery stable.)

When she agrees to have dinner with him, he lets her have an hour “to change and get fixed up.” As soon as he is gone, she has a flashback to the bell tower, which reveals to the audience her complicity in the murder. At first, she intends to pack a suitcase and run away, after writing him a letter that confesses her participation in Gavin’s plan and, what was not part of the plan, falling in love with him. (Recall their passionate kiss in the livery stable.)

However, she tears up the stationary. She opts instead to stay and see whether he can love her as the working-class woman she really is, not the impersonator in high society she once was. This decision leads her to become an extreme woman in distress and, ultimately, to die in one of cinema’s most unexpected and unforgettable tragedies.

Because Scottie believes Madeleine is dead, yet is still haunted by his fixation on her, he obsessively transforms Judy (back) into Madeleine. He takes her shopping at Ransohoff’s department store in order to buy the exact gray suit, black dinner dress and brown shoes that Madeleine wore. Judy puts up resistance: “You’re looking for the suit she wore for me. You want me to be dressed like her…No, I won’t do it!” But he is unrelenting: “It can’t make that much difference to you…Judy, do this for me!” And he gets his way.

That evening, at his apartment, she is sitting at his desk, slumped over. He pours and offers her a drink, which she ignores. She tries to put up more of a fight than she did at Ransohoff’s, but again, to secure his love, she submits to his demands. This scene (and the film’s last scene) represent the zenith in film noir’s depiction of a woman in psychological distress.

“Why are you doing this? What good will it do?”

[He walks away to a window, with his back to her.] “I don’t know. I don’t know. No good, I guess. I don’t know.”

“I wish you’d leave me alone. I wanna go away!”

“You can, you know.”

“No, you, you wouldn’t let me. And, and I don’t wanna go.” [He walks back to her. She still looks down at the desk.]

“No, you, you wouldn’t let me. And, and I don’t wanna go.” [He walks back to her. She still looks down at the desk.]

“Oh, Judy. Judy, I tell you this. These past few days have been the first happy days I’ve known in a year.”

“I know. I know because I remind you of her [tears run down her cheeks] and not even that very much.”

[He comes around to face her and, leaning forward, he puts his hands on her cheeks.] “No, Judy, Judy, it’s you, too. There’s something in you….”

[He comes around to face her and, leaning forward, he puts his hands on her cheeks.] “No, Judy, Judy, it’s you, too. There’s something in you….”

[He steps away from her, turning his back on her.]

“You don’t even want to touch me.”

“Yes, yes, I do.”

[Her cheeks are still tear-stained.] “Couldn’t you like me? Just me the way I am?”

[Her cheeks are still tear-stained.] “Couldn’t you like me? Just me the way I am?”

[She stands up and moves toward him. They look at each other.] “When we first started out, it was good. We had fun. And then you started in on the clothes. Well, I’ll wear the darn clothes if you want me to. If you’ll, if you’ll just like me.”

[She stands up and moves toward him. They look at each other.] “When we first started out, it was good. We had fun. And then you started in on the clothes. Well, I’ll wear the darn clothes if you want me to. If you’ll, if you’ll just like me.”

[He raises his eyes and stares at her hair, which is auburn whereas Madeleine’s was platinum.] “The color of your hair.”

“Oh, no!” [She turns away and looks out the window, with her back to him.]

[He follows her.] “Judy, please. It can’t matter to you.”

[She turns around.] “If, if I let you change me, will it do it? If I do what you tell me…will you love me?”

[She turns around.] “If, if I let you change me, will it do it? If I do what you tell me…will you love me?”

“Yes.” [He steps close to her.] “Yes.” [He takes her hands in his and kisses the left one.]

“Yes.” [He steps close to her.] “Yes.” [He takes her hands in his and kisses the left one.]

“Fine. All right, then. I’ll do it. I don’t care anymore about me.” [They embrace, and then they sit by his fireplace.]

Judy tries to assert her independence, to have Scottie love her as herself, but it is hopeless. He is uncompromising, neither caring for her feelings nor her self-respect. So that she can keep him, she submits to a complete makeover of her appearance and wardrobe. Her former accent is brought back, too. Therefore, this transformation marks a removal of Judy’s working-class persona and a restoration of Madeleine’s bourgeois one.

Judy and Scottie’s romance, on his terms, is secure until she makes a grave mistake by absent-mindedly putting on the same necklace that had linked her with Carlotta. Once Scottie sees it, he grasps he has been tricked twice by the same woman. Yet the motive for Judy to become “Madeleine” is fundamentally different in each instance. The first Madeleine is a femme fatale, the co-conspirator with Gavin to bring off the perfect murder. The second Madeleine is a woman in distress, suffering to sacrifice her own self if it means Scottie will love her.

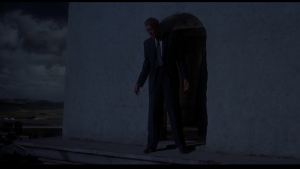

Without saying where they are going, he drives her to the Mission San Juan Bautista. When they arrive, Judy is uneasy about Scottie’s intentions. Her angst mounts as he makes her get out of the car and then pulls her with him to the bell tower, insisting that they go to the top together.

Without saying where they are going, he drives her to the Mission San Juan Bautista. When they arrive, Judy is uneasy about Scottie’s intentions. Her angst mounts as he makes her get out of the car and then pulls her with him to the bell tower, insisting that they go to the top together.

Every time she refuses to comply, he insists, and she gives in. But, when he looks down the staircase, it seemingly stretches and recedes farther away, just as it did on the day of the murder.

At the stair where his ailment kept him from following Madeleine, he says, “This is as far as I could get, but you went on. [She turns to look back at him.] The necklace, Madeleine. That was the slip. I remembered the necklace.”

At the stair where his ailment kept him from following Madeleine, he says, “This is as far as I could get, but you went on. [She turns to look back at him.] The necklace, Madeleine. That was the slip. I remembered the necklace.”

She tries to force her way past him, but he grabs her waist and drags her upward. (Scottie doesn’t experience acrophobia and vertigo.)

Higher up the stairs, he puts his hands on her throat and tells her what must have happened the day of the murder. He only asks whether the wife was “dead or alive.” She tries to break free, exclaiming, “Dead! dead! He’d broken her neck!”

Higher up the stairs, he puts his hands on her throat and tells her what must have happened the day of the murder. He only asks whether the wife was “dead or alive.” She tries to break free, exclaiming, “Dead! dead! He’d broken her neck!”

With each stair, his rage continues, unleashing one accusation against her after another.

When they get to the top, he looks down. This time there is no depiction of the staircase seemingly stretching and receding. Realizing that he is cured of his ailment, he pulls her up through a trap door into the belfry.

When they get to the top, he looks down. This time there is no depiction of the staircase seemingly stretching and receding. Realizing that he is cured of his ailment, he pulls her up through a trap door into the belfry.

As he asks her about being “ditched” by Gavin, he steps toward her, and she, frightened, backs away.

As he asks her about being “ditched” by Gavin, he steps toward her, and she, frightened, backs away.

She cowers in a corner as he admonishes her about saving Carlotta’s necklace.

She cowers in a corner as he admonishes her about saving Carlotta’s necklace.

“There’s where you made your mistake, Judy. You shouldn’t keep souvenirs of a killing. You shouldn’t have been [he chokes with emotion]…you shouldn’t have been that sentimental.”

In anguish, he says, “I loved you so, Madeleine.

She, too, is in anguish, both about what she did before and about losing him now. As she replies, begging for his love, the camera alternates between her pleading look and Scottie’s tormented one.

“Scottie, I was safe when you found me. There was nothing that you could prove. When I saw you again, I couldn’t run away, I loved you so. I walked into danger, let you change me, because I loved you, and I wanted you. Oh, Scottie. Oh, Scottie, please. You love me now. Keep me safe.”

She moves toward him. Standing next to him, she takes him in her arms, resting her head on his left shoulder.

She moves toward him. Standing next to him, she takes him in her arms, resting her head on his left shoulder.

He says, “Too late. It’s too late. There’s no bringing her back.”

She leans back, looking into his eyes, and says, “Please.”

For once Scottie doesn’t dismiss what Judy asks for. Clinging to each other, they kiss.

Judy’s passion for Scottie’s love and forgiveness triumphs over his intent to humiliate and take revenge on her. This woman’s victory needs to be explained because film critics and historians have instead dwelled on the transformation of Judy into Madeleine, first by Gavin, next especially by Scottie. What they haven’t addressed is that, when it counts the most, Judy transforms Scottie. As his aggression toward her wanes into sadness, she speaks up to justify herself. Until that moment, his complex range of feelings – from fury to grief – was surely going to lead to his separation from her. Instead, she convinces him to keep her, not reject her. In doing so, she saves him from himself. When he gives in to her pleas, he gets what he desires more than anything else: the woman who, despite looking like Madeleine, he now accepts and loves as Judy. After allowing herself to be made over by Scottie so that he can satisfy his own needs, Judy resists when losing him is imminent. That Judy stands up to Scottie, overcomes his forcefulness with her own willpower and redirects his emotions to satisfy her needs, is the superb climax of their relationship. Indeed, how fitting is it that Judy turns the tables on Scottie and makes him be what she has craved all along: the man who adores her for herself.

With their reconciliation, Scottie casts aside the fevered emotions he had felt for twice falling in love with an accomplice to a murder, as well as realizing the killing was successful because he had been duped by Judy into believing she was Gavin’s wife. As he acknowledges, there is no bringing back the real Madeleine. So, confronted with either abandoning Judy (and perhaps turning her over to the law) or resuming their romance, Scottie opts for letting Judy get off scot-free. Thus, a guilty woman – Scottie’s own femme fatale – wins over the former police detective into getting in bed with her, literally and figuratively. The heretofore innocent Scottie becomes a guilty party. Scottie’s acquiescence to Judy’s pleas that overcome his antagonism toward her and make him love her again perforce mean that he accepts joining her in culpability for guilt of the real Madeleine’s murder and, most significantly, turning a blind eye to their mutual culpability.

Yet it is so fleeting. Suddenly, spooked by the voice of an unseen shadowy figure (a nun who has ascended a different set of stairs to enter the belfry), Judy steps back, screams and falls off the tower.

Scottie stands outside the tower and looks down at her lifeless body. A second or two later, Vertigo ends.

What are we to make of Scottie at this moment? From his facial expression, it might be interpreted that for the third time in the film he is traumatized. In the opening scene, when he first experiences acrophobia and vertigo, he is traumatized from his sense of being responsible for a policeman falling to death.

Later on, Scottie has a nightmare that causes a nervous breakdown. He is traumatized for the same reason as before: he believes his acrophobia and vertigo made him responsible for Madeleine’s death. At the end, because Scottie doesn’t experience acrophobia and vertigo, he is able to drag Judy to the top of the bell tower. Had he experienced it and they had their confrontation, they would have been below on the stairway – and she wouldn’t have plunged from the belfry.

Later on, Scottie has a nightmare that causes a nervous breakdown. He is traumatized for the same reason as before: he believes his acrophobia and vertigo made him responsible for Madeleine’s death. At the end, because Scottie doesn’t experience acrophobia and vertigo, he is able to drag Judy to the top of the bell tower. Had he experienced it and they had their confrontation, they would have been below on the stairway – and she wouldn’t have plunged from the belfry.

Since we aren’t shown anything after Scottie sees Judy’s corpse, we can’t know whether he is traumatized a third time. However, we are aware of the finale’s bitter irony: Judy’s death can occur because Scottie is free from acrophobia and vertigo.

VI. An Interpretation of the End of Vertigo

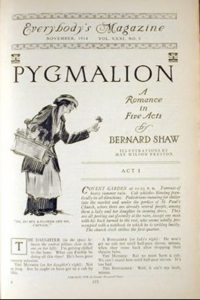

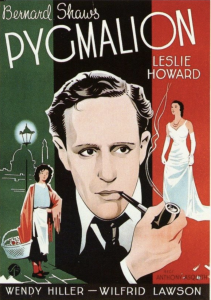

The tragic conclusion of Vertigo is in marked contrast to the principal antecedents of its storyline: the Greek myth about Pygmalion, made famous by the Roman poet, Ovid, in book X of his epic, Metamorphoses (completed by AD 8), and the play, Pygmalion, by the British dramatist, Bernard Shaw, which was first publicly staged in 1913.

In the myth, Pygmalion is a sculptor on the island of Cyprus. After carving a woman out of ivory, he falls in love with his beautiful creation. In 1762, French author Jean-Jacques Rousseau named the statue, Galatea (in Greek, “she who is milk white”), although in Greek mythology and in book XIII of Ovid’s Metamorphoses Galatea is central to a different story, and she is a sea nymph. In any case, since the late eighteenth century, Galatea has been associated with the ivory sculpture that the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite, brings to life to grant Pygmalion’s wish for a wife in the image of his statute. This story is depicted in the 1890 painting Pygmalion and Galatea by Jean-Léon Gérôme, an officially honored French painter and sculptor associated with the fin de siècle movements of academicism and Orientalism.

In the myth, Pygmalion is a sculptor on the island of Cyprus. After carving a woman out of ivory, he falls in love with his beautiful creation. In 1762, French author Jean-Jacques Rousseau named the statue, Galatea (in Greek, “she who is milk white”), although in Greek mythology and in book XIII of Ovid’s Metamorphoses Galatea is central to a different story, and she is a sea nymph. In any case, since the late eighteenth century, Galatea has been associated with the ivory sculpture that the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite, brings to life to grant Pygmalion’s wish for a wife in the image of his statute. This story is depicted in the 1890 painting Pygmalion and Galatea by Jean-Léon Gérôme, an officially honored French painter and sculptor associated with the fin de siècle movements of academicism and Orientalism.

In the play, Henry Higgins is a professor of phonetics and a misogynist. He brags that, by teaching a poor girl who sells flowers in London’s streets to speak proper English, he can convince people of high society she is “a duchess.” The flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, wants him to make good on his boast because, if he is successful, she can get hired in “a florist shop” and be done with the streets. Higgins succeeds, but he and Eliza are so disagreeable with each other that they can’t form a friendship, much less have a love affair. In the climax, Eliza’s self-confidence impresses him: “By George, Eliza, I said I’d make a woman of you; and I have. I like you like this.” But it is too late. She retorts, “Yes: you turn round and make up to me now that I’m not afraid of you, and can do without you.” The play ends with Eliza going away. Shaw steadfastly rejected criticism about the lack a happy ending in which Eliza marries Higgins. He wanted his Galatea to stay independent.

In the play, Henry Higgins is a professor of phonetics and a misogynist. He brags that, by teaching a poor girl who sells flowers in London’s streets to speak proper English, he can convince people of high society she is “a duchess.” The flower girl, Eliza Doolittle, wants him to make good on his boast because, if he is successful, she can get hired in “a florist shop” and be done with the streets. Higgins succeeds, but he and Eliza are so disagreeable with each other that they can’t form a friendship, much less have a love affair. In the climax, Eliza’s self-confidence impresses him: “By George, Eliza, I said I’d make a woman of you; and I have. I like you like this.” But it is too late. She retorts, “Yes: you turn round and make up to me now that I’m not afraid of you, and can do without you.” The play ends with Eliza going away. Shaw steadfastly rejected criticism about the lack a happy ending in which Eliza marries Higgins. He wanted his Galatea to stay independent.

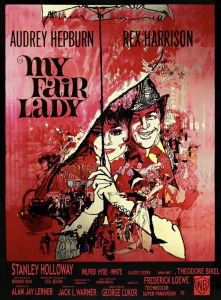

In the film, Pygmalion (1938, UK), the same exchange in the play occurs between Eliza and Higgins. But Eliza doesn’t leave alone; she rides off in a convertible driven by Freddy, a young gentleman who is crazy about her. Soon though, in the final scene, Eliza comes back to Higgins’s house. Co-directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, it was a financial hit, winning Bernard Shaw an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. It also influenced the Broadway musical, My Fair Lady (1956), with book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Lowe. Like that film (but not the play), after the showdown between Eliza and Higgins, she walks out, spends time with Freddy, then returns to the professor. What their future will be is anyone’s guess. This ambiguous conclusion is retained in the Hollywood version of My Fair Lady (1964), which won eight Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director for George Cukor.

In the film, Pygmalion (1938, UK), the same exchange in the play occurs between Eliza and Higgins. But Eliza doesn’t leave alone; she rides off in a convertible driven by Freddy, a young gentleman who is crazy about her. Soon though, in the final scene, Eliza comes back to Higgins’s house. Co-directed by Anthony Asquith and Leslie Howard, it was a financial hit, winning Bernard Shaw an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. It also influenced the Broadway musical, My Fair Lady (1956), with book and lyrics by Alan Jay Lerner and music by Frederick Lowe. Like that film (but not the play), after the showdown between Eliza and Higgins, she walks out, spends time with Freddy, then returns to the professor. What their future will be is anyone’s guess. This ambiguous conclusion is retained in the Hollywood version of My Fair Lady (1964), which won eight Oscars, including Best Picture and Best Director for George Cukor.

In Vertigo, Judy may be twice transformed into Madeleine, but only for Scottie is she his Galatea. For Gavin, she is “the tool” he designs to render Scottie the key witness to something that, in fact, he doesn’t see: the supposed suicide of Gavin’s wife. For Scottie, Judy is a romantic obsession, but only in the guise of being Madeleine. In contrast to Eliza’s dealings with Higgins, Judy’s experience vis-à-vis her Pygmalion, Scottie, is not only fundamentally different, it also suggests an interpretation to explain why Vertigo ends tragically.

First, in the play, musical and films, Eliza seeks out Higgins to teach her to speak English “more genteel.” She overhears him claim that, if she improves her speech she could “get her a place as lady’s maid or shop assistant,” which “requires better English” than being a duchess. The next day she goes to his house and offers to pay for her lessons. By changing how she talks – her diction and accent – Eliza knows she will be able to raise her employment prospects. Because of her commitment to moving up the class ladder, she endures Higgins’s insults, while railing right back at him. Judy, on the other hand, despairs of being changed into Madeleine, whose fashionable clothes, hair color, hairstyle, and manner of speech identify her as upper class. Judy is pleased with being and sounding working class.

First, in the play, musical and films, Eliza seeks out Higgins to teach her to speak English “more genteel.” She overhears him claim that, if she improves her speech she could “get her a place as lady’s maid or shop assistant,” which “requires better English” than being a duchess. The next day she goes to his house and offers to pay for her lessons. By changing how she talks – her diction and accent – Eliza knows she will be able to raise her employment prospects. Because of her commitment to moving up the class ladder, she endures Higgins’s insults, while railing right back at him. Judy, on the other hand, despairs of being changed into Madeleine, whose fashionable clothes, hair color, hairstyle, and manner of speech identify her as upper class. Judy is pleased with being and sounding working class.

Second, in Pygmalion the film, as well as My Fair Lady, the revised conclusion from Shaw’s play means that, instead of Eliza and Higgins being apart (seemingly for good), they are reunited after a brief separation. Yet they aren’t reconciled. In the last scene, Higgins is listening to one of his early recordings of Eliza’s speech when, unseen by him, she enters his room and speaks. As soon as he realizes she has returned, with his back to her, he says, “Where the devil are my slippers?” Their standoff resumes. It remains to be seen whether she will still do his bidding (like getting his slippers and running his errands), just as it is unknown whether she will ever change his “nature” and “manners.” As she had wanted, he changed her way of speaking. However, the musical and the films end without Eliza changing Higgins. That is, she doesn’t alter his behavior like Judy does to Scottie in their confrontation in the belfry.

Whatever the intentions of the screenwriters, or the director, the end of Vertigo reveals the film as a cautionary tale not only of the immorality but also the risk taken in a man’s domination of a woman. It won’t do to say that Judy’s demise is justice served for her role in the murder of Gavin’s wife, since there is no indication that Gavin himself will ever be arrested. There has to be some logical reason to explain the cause of her death, one that eschews the trivial, namely that she gets fatally frightened by the sudden arrival of the nun in the belfry and hearing her voice from out of the darkness. The explanation lies in Scottie’s blame for having Judy at the bell tower in the first place.

Pygmalion’s reward is a living woman, whereas Scottie’s ambition to transform Judy results in her being a corpse, as cold as an ivory statue. Judy may initially resist each of Scottie’s demands to mold her into Madeleine. However, they don’t wage a battle of the sexes on a level plane, like Eliza and Higgins, because Judy concedes to Scottie every time. Still, Scottie’s victory is Pyrrhic. It can hardly be Judy’s fault that she dons the necklace that gives her away. It is an innocent error. But the consequence of the retribution Scottie metes out to Judy, after he takes her back to Mission San Juan Bautista, is absolutely his responsibility. Had he respected her and her longing – to accept her as she is – he wouldn’t have lost her. Instead, he insists on controlling her and making her his Galatea. In his last words to her, Scottie is thinking about Gavin’s wife, yet he foretells Judy’s doom: “Too late. It’s too late. There’s no bringing her back.” Moments later, there is no bringing Judy back.

VII. Judy’s Flashback & Letter of Confession Intensify Her as a Woman in Distress

Above, I briefly describe a four-minute scene when Judy has a flashback and writes a letter of confession to Scottie, which she tears up at the end. Whether to include the scene – revealing early on to the audience, but not to Scottie, that Judy was/is Madeleine and, therefore, she had been Gavin’s partner in sex and murder – was very controversial.

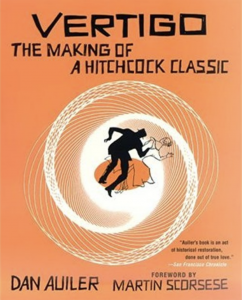

Dan Auiler, in Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000) discusses “a real fight” between Alfred Hitchcock, director and producer, and Herbert Coleman, associate producer, after a screening of the film without the scene. Coleman wanted the scene kept in, and Hitchcock wanted it out. Since Hitchcock owned the film, he got his way. However, the scene was in the prints that had already gone to movie theaters.

Dan Auiler, in Vertigo: The Making of a Hitchcock Classic (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2000) discusses “a real fight” between Alfred Hitchcock, director and producer, and Herbert Coleman, associate producer, after a screening of the film without the scene. Coleman wanted the scene kept in, and Hitchcock wanted it out. Since Hitchcock owned the film, he got his way. However, the scene was in the prints that had already gone to movie theaters.

In an interview with Auiler, Coleman said, “I had to call all the prints back that we had sent all over the country and recut the scene and redo the music and everything and send those out.” Meanwhile, Barney Balaban, the president of Paramount, not only wanted the scene included, he thought it was still in the film.

Then, Coleman told Auiler, Balaban found out the hard way that it had been deleted. He “had a run-in with the critics in New York. They told him he was crazy – it was the worst Hitchcock film ever made. He called us up in the studio and I thought we were all going to get fired – I thought the studio was going to get burned down. And he ordered that the scene be put back, so I had to call everyone back in again and redo the whole damn thing.” (160-161)

The inclusion of the flashback and confession reinforces Judy as a woman in distress. Because viewers know her past, they have to see her very differently than if they were only to learn the truth at the end.

For example, as I note above, on two occasions Scottie pressures Judy to change her appearance. First, at Ransohoff’s department store (about the gray suit) and, second, at his apartment (about the platinum hair color). Each time Scottie insists to Judy “it can’t matter.” What Scottie means is that, because he believes Judy is a different woman, she should have no emotional basis to oppose dressing and looking like someone she has never known or even seen. Yet, since the audience knows Judy wants to be loved as herself, her resistance and her tears can be understood and empathized with. Scottie, ignorant about her, cannot do so. Therefore, Judy’s unhappiness, and her eventual concessions to Scottie, underscore to viewers how intensely she is a woman in distress.

Despite her agreement with Scottie to change her hair, she violates it to retain something of her own self. At a hair salon, Scottie’s instructions indicate he wants Judy’s hair not only to replicate Madeleine’s in color but also in style. Nevertheless, when she comes back to her apartment, where he has been waiting, her hair only has a new color; the style remains as it was, with bangs. Scottie immediately notices it and complains. Annoyed by him, Judy turns away and says, “We tried it. It just didn’t seem to suit me.” Scottie softly says, “Please, Judy.”

Downcast, Judy silently assents and goes to her bathroom. Just before she opens the door, she raises her right hand and touches the bangs on her forehead, as though to give them a final acknowledgment, as they are the only remaining feature of her real self. Here the audience recognizes that no matter what Judy does to ward off total effacement of who she is, Scottie’s approval means more and, thus, wins out.

Downcast, Judy silently assents and goes to her bathroom. Just before she opens the door, she raises her right hand and touches the bangs on her forehead, as though to give them a final acknowledgment, as they are the only remaining feature of her real self. Here the audience recognizes that no matter what Judy does to ward off total effacement of who she is, Scottie’s approval means more and, thus, wins out.

When Judy, now completely remolded into Madeleine, emerges from her bathroom and walks toward Scottie, there can be, again, a distinction between Scottie’s reaction and that of the audience. To Scottie, Judy has become exactly what he wants, a woman who outwardly replicates one he loved and thinks he lost. In contrast, viewers realize how far Judy has gone for Scottie’s heart. If they were still in the dark about Judy and believed she were a different woman from Scottie’s Madeleine, someone who had only altered her attire and appearance, they might share Scottie’s pleasure. That is, if she were actually a different woman, the audience would have no insight into Judy’s feelings.

But, because of the flashback/confession, viewers are keenly aware of the cause of Judy’s hurt. They know she abandoned what she desired, to be herself. As they watch her walk toward Scottie, they don’t see a mere figure, a female objectified, but instead they see a flesh and blood woman, who has accepted making a tragic exchange: her own self for another’s love. The audience’s knowledge about Judy heightens her as a woman in distress, which could not occur with the excision of the controversial scene.

But, because of the flashback/confession, viewers are keenly aware of the cause of Judy’s hurt. They know she abandoned what she desired, to be herself. As they watch her walk toward Scottie, they don’t see a mere figure, a female objectified, but instead they see a flesh and blood woman, who has accepted making a tragic exchange: her own self for another’s love. The audience’s knowledge about Judy heightens her as a woman in distress, which could not occur with the excision of the controversial scene.

VIII. A Speculation about Scottie’s Nightmare

After the coroner’s inquest, Scottie visits Madeleine’s grave. That night he is seen in bed. What follows is an extraordinary depiction, in sight and sound, of his nightmare. Is there any significance to the images and scenes that are presented to the audience? Could they be clues to interpret Scottie’s nightmare? Regardless of whether it is intentional, I believe they can provide the audience with a tip-off about what is to come in the plot.

After the coroner’s inquest, Scottie visits Madeleine’s grave. That night he is seen in bed. What follows is an extraordinary depiction, in sight and sound, of his nightmare. Is there any significance to the images and scenes that are presented to the audience? Could they be clues to interpret Scottie’s nightmare? Regardless of whether it is intentional, I believe they can provide the audience with a tip-off about what is to come in the plot.

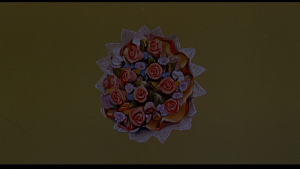

First, there is an image of a nosegay. (Madeleine buys one at the Podesta Baldocchi flower store when Scottie begins following her. It matches what Carlotta holds in the “Portrait of Carlotta.” It is with her as she stares at the painting at the art museum at the Legion of Honor. She throws its flowers into the bay before she jumps into the water.) Abruptly, the image becomes animated and splinters into multi-colored fragments.

First, there is an image of a nosegay. (Madeleine buys one at the Podesta Baldocchi flower store when Scottie begins following her. It matches what Carlotta holds in the “Portrait of Carlotta.” It is with her as she stares at the painting at the art museum at the Legion of Honor. She throws its flowers into the bay before she jumps into the water.) Abruptly, the image becomes animated and splinters into multi-colored fragments.

Next, there is a scene in which, as it were, Carlotta’s portrait comes to life as an actual woman. Gavin is holding her, and she is standing between Gavin and Scottie in front of the window in the second-floor room in the building where the coroner’s inquest takes place at Mission San Juan Bautista.

Next, there is a scene in which, as it were, Carlotta’s portrait comes to life as an actual woman. Gavin is holding her, and she is standing between Gavin and Scottie in front of the window in the second-floor room in the building where the coroner’s inquest takes place at Mission San Juan Bautista.

The image of Gavin with his right hand on Carlotta’s left arm recalls Gavin’s departure from Scottie after the conclusion of the inquest. Gavin says, “I’m getting out, Scottie, for good. I can’t stay here. I’ll wind up her affairs and mine…get away as fast as I can. Europe perhaps. I probably never will come back. Goodbye, Scottie.” (Gavin extends his right hand, but Scottie just looks down at it. Gavin then places his right hand on Scottie’s left arm.)

The image of Gavin with his right hand on Carlotta’s left arm recalls Gavin’s departure from Scottie after the conclusion of the inquest. Gavin says, “I’m getting out, Scottie, for good. I can’t stay here. I’ll wind up her affairs and mine…get away as fast as I can. Europe perhaps. I probably never will come back. Goodbye, Scottie.” (Gavin extends his right hand, but Scottie just looks down at it. Gavin then places his right hand on Scottie’s left arm.)

Gavin says, “If there’s anything I can do for you before I go….” (He drops his arm and looks back into the room, which only minutes before had been full of people at the inquest.) “There’s no way for them to understand.” (He turns back to look at Scottie.) “You and I know who killed Madeleine.” (He walks away.)

After this scene, the same woman is shown in Carlotta’s pose in the painting. The camera zooms in to a close-up of the necklace.

Next, Scottie walks in the cemetery of the Mission Dolores Church, where he once followed Madeleine when she visited Carlotta’s grave. (In her made-up dream, Madeleine says there is “an open grave. I stand by the gravestone looking down into it. It’s my grave.” He asks, “How do you know?” She replies, “I know.” He asks if there is a name on the gravestone. She says, “No, but it’s new, clean and waiting.”) In the nightmare there is an open grave, but the gravestone is Carlotta’s.

Next, Scottie walks in the cemetery of the Mission Dolores Church, where he once followed Madeleine when she visited Carlotta’s grave. (In her made-up dream, Madeleine says there is “an open grave. I stand by the gravestone looking down into it. It’s my grave.” He asks, “How do you know?” She replies, “I know.” He asks if there is a name on the gravestone. She says, “No, but it’s new, clean and waiting.”) In the nightmare there is an open grave, but the gravestone is Carlotta’s.

Now, unless Scottie is visualizing his own face, moving forward, against changing colors, the film stops depicting his nightmare and, instead, represents to the audience his psychological torment.

Now, unless Scottie is visualizing his own face, moving forward, against changing colors, the film stops depicting his nightmare and, instead, represents to the audience his psychological torment.

The film returns to the nightmare and concludes it with Scottie’s figure plummeting down, first toward the roof on which the real Madeleine’s body landed, then into empty space, nothingness.

The film returns to the nightmare and concludes it with Scottie’s figure plummeting down, first toward the roof on which the real Madeleine’s body landed, then into empty space, nothingness.

Although the images and scenes supposedly originate in the subconscious of the ex-police detective, Scottie isn’t real, of course. Therefore, they are created for the film’s viewers. I think they can be interpreted in a way that is justifiable by the evidence, even if it may not have been intended.

Most revealing are two scenes that I speculate raise questions about Madeleine’s death. First, there is the scene with the woman who resembles Carlotta. It crucially alters the one in front of the same window after the inquest.

In their first meeting at Gavin’s office, to explain why he wants Scottie to follow his wife, Gavin says he is “afraid some harm may come to her” from “someone dead…out of the past…[who] can enter and take possession of [her].” After the inquest, it may be that Gavin is referring to (his fabrication of) Carlotta as a threat to his wife when he tells Scottie that others can’t “understand,” but he and Scottie “know who killed Madeleine.” Thus, by alluding to Madeleine’s death as the result of supernaturalism, Gavin may be trying to reinforce in Scottie’s mind the legitimacy of his fabrication.

However, the scene in the nightmare contradicts this. Gavin stands near the woman, with his right hand on her left arm (his left hand isn’t shown). She doesn’t appear to be dangerous as she ought to if Scottie were going to imagine her as who (or what) “killed” his beloved Madeleine. After the inquest, Gavin gets no response when he reaches out his hand to Scottie, but in the nightmare Gavin’s hand on the woman indicates there is something meaningful between them. I speculate this scene can be interpreted that Carlotta isn’t as Gavin has made her out to be – the dead person responsible Madeleine’s death.

Second, the scene with the grave contradicts Madeleine’s description of an open grave, whose location she doesn’t know, which she says is hers, and which has a “new, clean” gravestone without a name on it. The scene specifically places the grave in the Mission Dolores Church’s cemetery. Because the gravestone is explicitly Carlotta’s, it is not new, not clean and not nameless. Based on these many discrepancies, I speculate that the open grave can be interpreted as one that isn’t associated with Madeleine. This scene suggests Madeleine cannot be buried in it because she isn’t dead.

From these two scenes, I speculate Scottie’s nightmare contains clues that suggest Madeleine is alive.

Consider the image of the woman shown in Carlotta’s pose in the painting, and the camera zooming to a close-up of the necklace. Before this point in the film, there has been no significance given to the necklace.

After following Madeleine to the Legion of Honor, Scottie sees the “Portrait of Carlotta.” There are two close-ups of features in the painting (what Scottie focuses on): the nosegay, which matches the one on the bench next to Madeleine, and a swirl in Carlotta’s hair, which matches one in Madeleine’s hair. A shot of the upper half of Carlotta indicates she is wearing a necklace, but no emphasis is given to it. (Madeleine is not wearing such a necklace.)

After following Madeleine to the Legion of Honor, Scottie sees the “Portrait of Carlotta.” There are two close-ups of features in the painting (what Scottie focuses on): the nosegay, which matches the one on the bench next to Madeleine, and a swirl in Carlotta’s hair, which matches one in Madeleine’s hair. A shot of the upper half of Carlotta indicates she is wearing a necklace, but no emphasis is given to it. (Madeleine is not wearing such a necklace.)

Later, Gavin tells Scottie that Madeleine “has several pieces of jewelry that belonged to Carlotta. She inherited them. Never wore them. They were too old-fashioned. Until now. Now when she’s alone, she takes them out and looks at them. Handles them gently, curiously. Puts them on and stares at herself in the mirror. Then goes into that other world, as someone else again.” Gavin doesn’t mention a necklace; instead he refers to the plural of pieces of jewelry.

Later, Gavin tells Scottie that Madeleine “has several pieces of jewelry that belonged to Carlotta. She inherited them. Never wore them. They were too old-fashioned. Until now. Now when she’s alone, she takes them out and looks at them. Handles them gently, curiously. Puts them on and stares at herself in the mirror. Then goes into that other world, as someone else again.” Gavin doesn’t mention a necklace; instead he refers to the plural of pieces of jewelry.

Why is there a close-up of the necklace? Since Scottie doesn’t focus on it at the museum, it is doubtful he can recall, in detail, what it looks like. I think the close-up is meant to bring the necklace to the attention of the audience and to establish that Scottie is aware of it. Thus, when he sees it around Judy’s neck, not only will it make sense that he remembers it, but also the audience will be able to accept that it signifies to him that Judy is Madeleine.

Why is there a close-up of the necklace? Since Scottie doesn’t focus on it at the museum, it is doubtful he can recall, in detail, what it looks like. I think the close-up is meant to bring the necklace to the attention of the audience and to establish that Scottie is aware of it. Thus, when he sees it around Judy’s neck, not only will it make sense that he remembers it, but also the audience will be able to accept that it signifies to him that Judy is Madeleine.

This close-up surely seems created for and directed to the audience. Accordingly, I believe it is fair to speculate that other images and scenes in the nightmare are created for the audience and, of course, they don’t come from Scottie’s imagination.

When Scottie suddenly wakes up, seemingly terrified, he has had a nervous breakdown. He slowly recovers in a sanitarium. A doctor says he “is suffering from acute melancholia, together with a guilt complex. He blames himself for what went on with the woman.” Plus, of course, Scottie is still in love with her.

When Scottie suddenly wakes up, seemingly terrified, he has had a nervous breakdown. He slowly recovers in a sanitarium. A doctor says he “is suffering from acute melancholia, together with a guilt complex. He blames himself for what went on with the woman.” Plus, of course, Scottie is still in love with her.

After his release, he haunts places he associates with Madeleine: the Bronklebank Apartments (where she lived), Ernie’s restaurant, the Legion of Honor. He is looking at a nosegay in the window of the Podesta Baldocchi flower store when he first sees Judy walking in his direction. He follows her to her apartment. Then Vertigo becomes about the nonpareil woman in psychological distress.

After his release, he haunts places he associates with Madeleine: the Bronklebank Apartments (where she lived), Ernie’s restaurant, the Legion of Honor. He is looking at a nosegay in the window of the Podesta Baldocchi flower store when he first sees Judy walking in his direction. He follows her to her apartment. Then Vertigo becomes about the nonpareil woman in psychological distress.

IX. The Other Woman in (Psychological) Distress in Vertigo

There are several scenes that show Midge Wood, initially Scottie’s close friend and confidant, as an agonized woman. At the end of nearly every one of these scenes, she is unhappy if not distraught. Despite my brief descriptions, I want to bring attention to the other woman in Vertigo who suffers psychological distress. Among the points of interest is that Midge shares with Judy the same source of plight, a profound but self-endangering love for Scottie. With Judy, this is the crux of her confrontation with him in the belfry. With Midge, besides forgoing marriage, her final image suggests something bleaker about her future.

Midge tells Scottie that he is “the only one man in the world” for her. Since he won’t marry her, she seems resigned to being a spinster. Scottie is oblivious to how much she loves him, and how he so easily hurts her, such as saying she was the one who called off their three-week engagement in college. Failing to show her how he can overcome his acrophobia, he falls off a step-stool and collapses into her arms. The scene ends with Midge miserable.

Midge tells Scottie that he is “the only one man in the world” for her. Since he won’t marry her, she seems resigned to being a spinster. Scottie is oblivious to how much she loves him, and how he so easily hurts her, such as saying she was the one who called off their three-week engagement in college. Failing to show her how he can overcome his acrophobia, he falls off a step-stool and collapses into her arms. The scene ends with Midge miserable.

As Madeleine leaves Scottie’s apartment, following his “rescue” of her in the San Francisco Bay, Midge is driving by and sees her. She stops and watches Madeleine get in her own car and drive off. Assuming the worst, that Scottie and Madeleine are having an affair, Midge slyly grins and says, “Well, now, Johnny-O, was it a ghost? Was it fun?” Scottie then opens his front door and sees Madeleine is gone. Midge drives away. This incident leads to her next scene with Scottie, as follows.

For a drink and dinner at her apartment, Scottie promises to take Midge to a movie. First, however, she wants him to look at a painting she has completed. As soon as he sees that she has painted herself as Carlotta, he says softly but firmly, “It’s not funny, Midge,” and walks out. Furious at herself, Midge defaces the painting, crying, “Idiot! Stupid! Stupid!”

For a drink and dinner at her apartment, Scottie promises to take Midge to a movie. First, however, she wants him to look at a painting she has completed. As soon as he sees that she has painted herself as Carlotta, he says softly but firmly, “It’s not funny, Midge,” and walks out. Furious at herself, Midge defaces the painting, crying, “Idiot! Stupid! Stupid!”

While Scottie is recovering from his mental breakdown, she tells his doctor that he is in love with a woman whose death he feels responsible for. She walks out of the doctor’s office and toward the end of a hallway. The lighting darkens, and the scene ends. With forty minutes remaining in Vertigo, Midge is out of the picture.

While Scottie is recovering from his mental breakdown, she tells his doctor that he is in love with a woman whose death he feels responsible for. She walks out of the doctor’s office and toward the end of a hallway. The lighting darkens, and the scene ends. With forty minutes remaining in Vertigo, Midge is out of the picture.

X. Additional Speculations

It seems fair to assume that the source of Judy’s psychological plight – Scottie’s erasure of her own identity – is a harbinger of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (W.W. Norton and Company, 1963), with its reporting, among other subjects, that American women were unhappy and “suffered the problem that has no name.”

It seems fair to assume that the source of Judy’s psychological plight – Scottie’s erasure of her own identity – is a harbinger of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (W.W. Norton and Company, 1963), with its reporting, among other subjects, that American women were unhappy and “suffered the problem that has no name.”

According to Wikipedia, “In 1957, Friedan was asked to conduct a survey of her former Smith College classmates for their 15th anniversary reunion; the results, in which she found that many of them were unhappy with their lives as housewives, prompted her to begin research for The Feminine Mystique, conducting interviews with other suburban housewives, as well as researching psychology, media, and advertising.” Friedan carried out her survey in the same year that the script for Vertigo was finalized. The writing and filming of Vertigo share the same historical moment as Freidan’s encounter with American women’s unhappiness, their psychological distress.

Also, it is fair to wonder if either screenwriter, Alec Coppel or Samuel A. Taylor, was influenced by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Lowe’s My Fair Lady, the 1957 Tony award-winning musical. Its long stage-run began in 1956, the year its Original Cast Recording was the best-selling album in the U.S., with eight weeks at #1 (and #1 for at least one week in the next three years). Given its huge dual commercial successes and, therefore, the enormous public awareness of it, the screenwriter(s) could hardly have been ignorant of this story of a man who changes a working-class woman’s speech, manners and attire so that she can pass as a “lady” of distinction. Did the screenwriter(s) draw on My Fair Lady for source material for Vertigo? Consider the following questions.

Also, it is fair to wonder if either screenwriter, Alec Coppel or Samuel A. Taylor, was influenced by Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Lowe’s My Fair Lady, the 1957 Tony award-winning musical. Its long stage-run began in 1956, the year its Original Cast Recording was the best-selling album in the U.S., with eight weeks at #1 (and #1 for at least one week in the next three years). Given its huge dual commercial successes and, therefore, the enormous public awareness of it, the screenwriter(s) could hardly have been ignorant of this story of a man who changes a working-class woman’s speech, manners and attire so that she can pass as a “lady” of distinction. Did the screenwriter(s) draw on My Fair Lady for source material for Vertigo? Consider the following questions.

Is Professor Henry Higgins’s makeover of Eliza Doolittle a prototype of Gavin and Scottie’s transformations of Judy into Madeleine?

Eliza, a girl who sells flowers on a London street corner, puts up with Higgins’s misogyny because he promises her that she will “learn to speak beautifully like a lady in a flower shop.” Is it merely a coincidence that a key location in Vertigo is Podesta Baldocci’s flower store, where Madeleine buys the nosegay she takes with her to the Legion of Honor and in front of which Scottie first sees Judy?

Is it coincidental that Scottie’s past history with women is like that of Henry Higgins’s, as well as the professor’s literary predecessor, Pygmalion? According to Ovid, until Pygmalion is smitten by his sculpture, he was “not interested in women.” Higgins has been “a confirmed old bachelor” before he meets Eliza, and at the heart of the ambiguity at the end of the films and the musical is whether he will remain so. Based on his interactions with Midge, Scottie has had no lasting romantic relationships (or sexual activity?) before he transforms Judy into Madeleine. (Once she completes her transformation by getting rid of her bangs, they apparently make love.)

The French crime novel on which Vertigo is based, D’Entre Les Morts (1954)/Vertigo (Dell, 1958; reprint Pushkin Vertigo 2015), by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, lacks essential similarities with the film. Most significantly, the man with vertigo, who is manipulated by Renée to be the witness to the wife’s “suicide,” may go about changing Renée into Madeleine after he accidentally finds her alive, but there isn’t much that he does. Although he buys her “a grey suit,” there is no transformation process. In the novel’s final few pages, when Renée admits to having impersonated the wife and being complicit in her murder, she makes no mention of being made over by the husband to resemble his wife in appearance and in social class. Perhaps the screenwriter(s) got brilliantly inspired by the novel to plot Scottie’s extensive transformation of Judy into Madeleine. Yet it seems justifiable to speculate that My Fair Lady was, instead, the source of that inspiration.

The French crime novel on which Vertigo is based, D’Entre Les Morts (1954)/Vertigo (Dell, 1958; reprint Pushkin Vertigo 2015), by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, lacks essential similarities with the film. Most significantly, the man with vertigo, who is manipulated by Renée to be the witness to the wife’s “suicide,” may go about changing Renée into Madeleine after he accidentally finds her alive, but there isn’t much that he does. Although he buys her “a grey suit,” there is no transformation process. In the novel’s final few pages, when Renée admits to having impersonated the wife and being complicit in her murder, she makes no mention of being made over by the husband to resemble his wife in appearance and in social class. Perhaps the screenwriter(s) got brilliantly inspired by the novel to plot Scottie’s extensive transformation of Judy into Madeleine. Yet it seems justifiable to speculate that My Fair Lady was, instead, the source of that inspiration.

Lastly, within crime fiction, is there a genre that Vertigo can be associated with? The most appropriate answer is the British sensation novel, which arose in the 1860s. Although it is beyond the scope of this examination of Vertigo to review in detail its affinities with the sensation novel, a sampling of important ones are as follows. The story isn’t set in the past but is fairly contemporary. Crime, such as murder, is within a bourgeois family/marriage. Plot elements include a hidden identity, fraud, a transgressing woman, infidelity/bigamy, a supernatural force, and madness. There may be detecting (by an amateur or a police officer), but it isn’t a detective tale per se. One sensation novel seems quite relevant to Vertigo. Among the earliest written, Mary Elizabeth Braddon’s Lady Audley’s Secret was a huge best-seller, and many editions are in print today, over 150 years after it was first published in 1862. Strikingly, it has plot features present in Vertigo but absent in D’Entre Les Morts. Three are addressed here.

The first pertains to Robert Audley, who is intent on proving that his elderly uncle’s young and beautiful wife has murdered his best friend (and her own first husband), George Talboys. Robert believes she killed George so that she wouldn’t have to give up her opulent lifestyle and aristocratic title, both achieved through marriage to Sir Michael Audley. Like Scottie, Robert has a dream that foreshadows a future revelation.

The second pertains to the specific way the dream foreshadows a future revelation. As noted above (VIII. A Speculation about Scottie’s Nightmare), Scottie’s dream includes an empty grave, which I speculate signals that Madeleine isn’t dead. Below is Braddon’s description of Robert’s dream.

“At one time he was pursuing strange people and entering strange houses in the endeavor to unravel the mystery of the telegraphic dispatch; at another time he was in the churchyard at Ventnor, gazing at the headstone George had ordered for the grave of his dead wife. Once in the long rambling mystery of these dreams he went to the grave, and found the headstone gone, and on remonstrating with the stonemason, was told that the man had a reason for removing the inscription, a reason that Robert would some day learn.” (Oxford University Press, 2012, 87).

The background to Robert’s dream is as follows. George abandoned his wife, Helen, to seek his fortune mining for gold in Australia. Poor yet ambitious, Helen left her village home and changed her name. Since she never heard from George during his absence, she could reasonably believe that he had passed away. Three and a half years after his departure, George returns to Britain richer by £20,000 ($2,026,225 in 2018). On seeing a notice in the paper about his homeward voyage and knowing that he will search everywhere for her, she schemes to have the natural death of a young woman be reported in the London Times as her own. As she anticipates, when George reads the notice, his heart breaks. He visits the grave, sees the headstone with Helen’s name on it, and accepts her death as fact. George then learns the truth because of two chance incidents. First, in London he happens to run into his old friend Robert. Second, when Robert visits his uncle, Sir Michael, George accompanies him, whereupon he discovers his wife is alive. Therefore, this is what Robert’s dream foreshadows: the inscription on the headstone, “HELEN, the Beloved Wife of George Talboys,” is removed because Helen still lives, as Lucy Audley.

It is fair to speculate whether Vertigo’s screenplay intentionally incorporates these two features from Lady Audley’s Secret: a dream by the protagonist that foreshadows, via imagery of a grave, that a woman he believes is dead, he will later discover is alive.

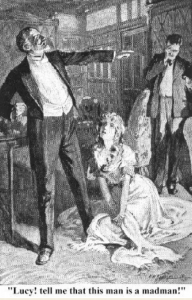

The third pertains to what is central to the plots of both Braddon’s novel and Hitchcock’s film, yet is never mentioned in D’Entre Les Morts. When Robert finally gets Lucy to confess to him, she cries out:

“You have conquered – a MADWOMAN!”

“A madwoman!” cried Mr. Audley.

“Yes, a madwoman. When you say that I killed George Talboys, you say the truth. When you say that I murdered him treacherously and foully, you lie. I killed him because I AM MAD!…Bring Sir Michael; and bring him quickly. If he is to be told one thing, let him be told everything; let him hear the secret of my life.” (294)

After Robert brings his uncle to hear her confession, Lucy tells him what she discovered as a youngster and how it became her secret of the book’s title.

“At last the secret came out. I worried my foster-mother with the old question one day [i.e., Where is my mother?]… She flew into a passion; and told me my mother was a madwoman; and that she was in a mad-house forty miles away…I brooded horribly about my mother’s madness. It haunted me by day and night…Before my father sent me to school at Torquay, he took me to see my mother…But she didn’t know us…Her madness was an hereditary disease transmitted to her from her mother, who had died mad. She, my mother, had been, or had appeared, sane up to the hour of my birth; but from that hour her intellect had decayed until she had become what I saw her. I went away with the knowledge of this, and with the knowledge that the only inheritance I had to expect from my mother was – insanity!” (296-298)

There is much more about madness in the novel. For example, when Lucy learns Robert has the proof to expose her, she plots to convince her devoted husband that Robert has lost his mind. Later, after Lucy’s confession to Sir Michael, Robert wants to avoid putting Lucy on trial; instead, he wants her committed to an asylum. He solicits an opinion about Lucy from a doctor whose “practice is almost confined to treatment of mental diseases.” (319) The doctor informs Robert that madness within a family may jump a generation. The trait, he says, may pass from a grandmother to her granddaughter. (321)

There is much more about madness in the novel. For example, when Lucy learns Robert has the proof to expose her, she plots to convince her devoted husband that Robert has lost his mind. Later, after Lucy’s confession to Sir Michael, Robert wants to avoid putting Lucy on trial; instead, he wants her committed to an asylum. He solicits an opinion about Lucy from a doctor whose “practice is almost confined to treatment of mental diseases.” (319) The doctor informs Robert that madness within a family may jump a generation. The trait, he says, may pass from a grandmother to her granddaughter. (321)

In Gavin’s murder scheme, apart from getting Scottie to fall in love with her, Madeleine’s key objective is to convince Scottie of her fear that she will inherit madness from her grandmother, Carlotta. Therefore, it is fair to speculate whether Vertigo’s screenplay intentionally incorporates this feature from Lady Audley’s Secret.

What connects Braddon’s novel to Lerner and Lowe’s Broadway musical and also to Hitchcock’s film is the demonstration of the permeabilty of social class. Helen is of the working class when she marries George Talboys. She enters the aristocracy when, as Lucy, she weds Sir Michael Audley. She has so much changed herself that he is unable to recognize her origins. Professor Higgins transforms Eliza’s accent from raw Cockney to such proper English that, at the Embassy Ball, she is considered by a Hungarian phonetician (“No imposter can escape my detection”) to be a Hungarian princess! In the opposite direction, proletarian Judy begins as patrician Madeleine. Scottie is later able to alter Judy back into Madeleine. All three plots show how so-called class distinctions can be successfully subverted. Yet in all three plots the class positions of men remain fixed, but for the leading woman in each story her class position is mutable. Furthermore, the essential aspect of each story is that very fact: her class mutability.

How she changes class is different in each story and, taken chronologically, her own agency progressively diminishes. Helen Talboys/Lucy Audley refashions herself because she wants to rise socially and there is no one else she would allow to help her. Eliza Doolittle is willing to pay a man, Henry Higgins, to remake her because she knows she cannot become a lady on her own. Two men sequentially (first Galvin Elster, then Scottie Ferguson) create Madeleine from Judy Barton. For Judy, the circumstances of her second time becoming Madeleine are far worse than her first. With Galvin, she willingly goes along with his murder scheme because she is deceived that he is in love with her. With Scottie, no matter how hard she tries to resist his entreaties that she keep doing one thing more to satisfy his craving that she be Madeleine again, she always gives in because his love for her is matched by hers for him.

The lives of Lucy and Judy finish tragically. But what of Eliza’s? Can we be positive about her prospects for an equitable relationship with the professor, given that the last words she and we hear are his bark, “Where the devil are my slippers?” At the conclusion of Shaw’s 1913 Pygmalion as well as some 21st. century productions of My Fair Lady, Eliza is separated from (independent of) Higgins. Regarding their future, it is understandable if we view the climax of the original show as ambiguous. However, we can also quite plausibly speculate that she will be nothing other than subsurvient to him (like fetching his slippers), thereby forfeiting her opportunity for autonomy. Rejecting this outcome, Shaw’s play and recent versions of the musical intentionally end otherwise. Since Lerner and Lowe (adhering to the change to the play in the 1938 film of Pygmalion) keep Eliza and Higgins together, the finale of their My Fair Lady is neither feminist nor markedly elevated above that of either Lady Audley’s Secret or Vertigo. In each of these three plots, an ambitious woman ascends the class ladder but ultimately doesn’t get what she wants.